By Melissa Barbieri

Twenty-five years ago I made my professional debut for Victoria in the old women’s national league. It was the first season of the new competition and the game was at the Veneto Club in Bulleen.

The Veneto Club is now astroturf but in 1997 it was beautiful green grass – one of the best pitches in Melbourne.

It felt extra special because that club banned me from playing when I was nine years old, saying that girls weren’t allowed to play football.

I carried a lot of anger through my teenage years, because that lie caused me to miss five crucial years of junior football. At 14, I found another club and returned to the game I fell in love with as a child.

Three years later and here I was, running out onto the main field at the Veneto Club, representing my state in a national competition. They banned me for being a girl but I returned as a woman.

That was the first time I proved someone wrong, but it wouldn’t be the last.

I just turned 42 and my career has been a constant struggle to prove myself to people who say it can’t be done.

But this isn’t a hard luck story. In fact, the timing of my negative experiences really helped to propel me to where I am today.

A lot of people don’t know that I am an accidental goalkeeper. I made my debut for Victoria in the No. 11 jersey, and the first time I was selected for a national team camp it was as a left winger.

I certainly didn’t want to become a goalkeeper, but I joined the keepers’ union so that I could stay in the game.

It all began in 2000, after I saw the Matildas play at the Sydney Olympics. Straight away I enlisted three or four coaches and started training like crazy.

I was working part-time at Sportsco, on my feet all day, and my left leg would go numb. I distinctly remember hearing a pop at work and thinking, that’s weird.

I didn’t have access to the best sports doctors, so I ended up at a surgeon who told me if it hurts to run around I should just stop playing.

I was shattered. I’d just decided my goal was to go to the Olympics, and now they’re telling me I can’t play at all?

I decided then and there to become a goalkeeper.

The biggest hurdle was convincing my coaches. Can you imagine it? Their best left-sided player, who they’d selected to bomb down the wing and whip balls into the box, suddenly insists on playing in goals – all the time.

Some of them tried to beat it out of me. Ernie Merrick threw me in against the boys at the Victorian Institute of Sport and had them shoot at me. By the end of the session I’d earned his respect.

Looking back, I did have some advantages. I grew up as a tomboy with brothers, so I got roughed up a lot. During my childhood exile from football I played basketball, so I knew how to jump and catch.

I was also very comfortable with the ball at my feet, and FIFA had just changed the rule so that goalkeepers couldn’t pick the ball up from a teammate’s throw-in or back-pass. I was a natural sweeper-keeper at a time when many goalkeepers were still adjusting to that rule.

It did take a while to get my bearings. Those early mistakes were often down to poor positioning or a split second of indecision because I didn’t know where I was in my goal or my box.

But I was already in the national team program so I had access to some of the best coaches. A former Socceroos goalkeeper, Jimmy Fraser, brought me into a camp and showed me how to dive.

When the pain in my leg came back, I got it scanned and they found it was just hamstring tendinitis. So I could have easily gone back to being a midfielder, but by that time my eyes were open to the fun that you can have in goals.

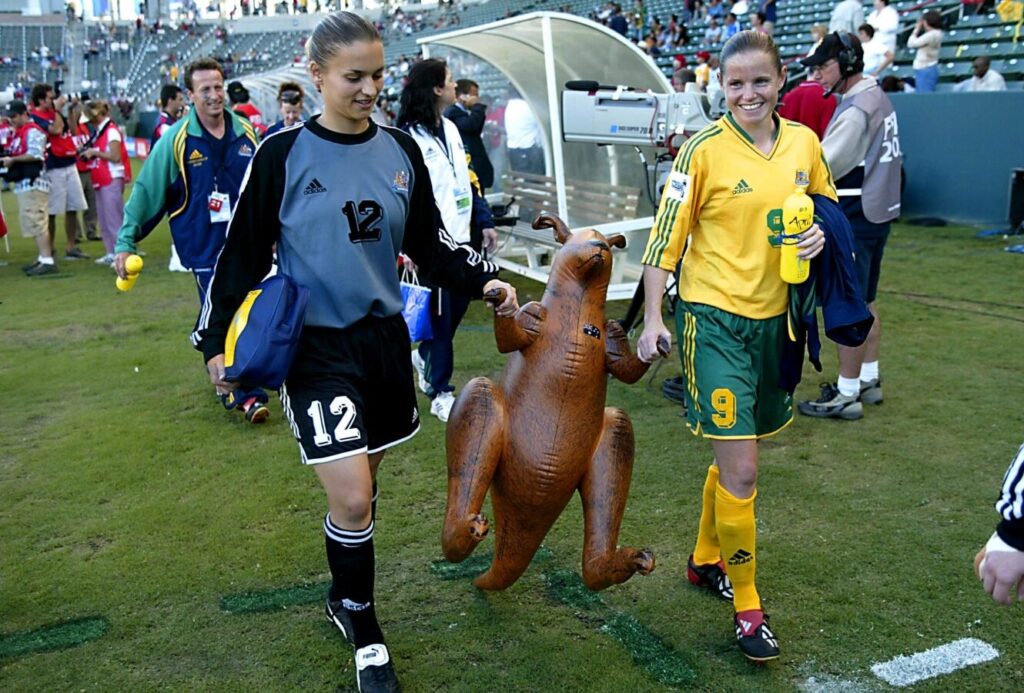

I kept a clean sheet on my senior debut for the Matildas in 2002, got picked for the 2004 Athens Olympics, captained Australia to our first Asian Cup victory in 2010 and played at four World Cups.

The other day, the A-Leagues’ statistician Andrew Howe sent me a complete list of every game of my career. Thanks to him, I now know that I’ve played more than 150 top flight matches and I‘m the oldest Australian – male or female – to play national league football.

That includes the old Ansett Summer Series. It might not have had the same spotlight as the W-League, but that competition was so important for my generation.

I wish some of these kids could have seen Di Alagich or Cheryl Salisbury or Julie Murray play. I think there’s a lot of VHS tapes out there that need to be dug out and downloaded.

Some of the players from that era got to play a season or two in the W-League, but it was really tough for many of us when the Ansett Summer Series finished in 2005.

That terrible break came right in the middle of my career, when I was in my mid-twenties. It was very difficult because I was a Victorian on my own – we didn’t have a lot of national team members or camps here.

I had to go back to the local competitions and ask a lot of favours. In 2007, I became the first woman to play in a men’s team in the old Victorian State League.

A year later, when the W-League kicked off, we made very little money but it was our first pay cheque as a domestic player. I’d been making a wage with the Matildas, but the difference was my mates could all make a wage now as well.

Some of them had already retired and moved on to other things, but I bugged them to come back and play just one more season.

Looking back on it now, shifting to goalkeeper has certainly prolonged my career. If I was still a midfielder I don’t think I’d be playing professionally in my forties.

Age has brought its own challenges. When my husband and I started a family in 2013, I lost my main source of income from the Victorian Institute of Sport and national team contracts.

People just wrote me off and expected me to retire, because the attitude was women with children don’t play professional sport.

It took me a long time to come back because Holly was breached and I went through an emergency C-section. But I’d seen children and nannies in camp when we played against the USA, so I knew it was possible.

I wrote to W-League clubs asking for another chance. When Ross Aloisi and Adelaide United threw me a lifeline, I sold my Matildas possessions to fund the season.

But then in 2016 I did my knee and once again everyone told me that was it. I was 36 with a young kid and I’d already retired from the Matildas.

How many times would it have been easier to just walk away from football? At nine, I was banned for being a girl. At 20, I was told to stop playing because of an injury. At 25, the old national league shut down. At 33, I was told mums don’t play professionally.

I wasn’t going to let a knee injury stop me. I didn’t want to go out like that.

I was fortunate that by the time I recovered, the PFA had negotiated a Collective Bargaining Agreement and we got a minimum wage and better medical standards. Not long after we signed the CBA I joined Melbourne City, the club I’m at today.

I’m constantly amazed at how professional things are at this club. I can’t get enough of it. Sometimes I think, where has this been all my life?

I’m going to stay and enjoy it for as long as I can – even if it means sitting on the bench. I just want to be a part of it so I can experience what we’ve fought for over the years.

A lot of people have told me to give it up and let the next generation take over. I’ve got a lot of confidence in the young players I see coming through the ranks, and I hope I am a good teammate and mentor to them.

In saying that, I’ve been fighting to play this game for longer than most of them have been alive, so I’m here to show the next generation that if they want it, they have to fight for it too.