By Marc Warren

At 17 I was a regular for the Joeys and life was a breeze. At 18 I signed my first professional contract and I could taste the bigtime. At 19 I was in a matchday squad in the Championship, watching teammates like Harry Maguire, and playing in the U-20 World Cup, sharing a pitch with Isco, Koke, and Sergi Roberto.

Three years later I was working in a warehouse, drinking too much, gambling with what little money I had, and unsure of my place in the world. If you’re not prepared, dreams can turn to nightmares in no time.

Ten years on from signing that first contract I understand myself a lot better. I know that my identity does not have to be defined by football and I’ve learned from my mistakes.

It all seems so uncomplicated when you’re a kid. Early on in my career all that mattered was football, all day, every day. The pathway from putting on my first pair of boots to leaving Australia’s finest football finishing school couldn’t have been more straightforward. This was my destiny.

The public aren’t exposed to the complications of having a professional career and things became challenging around 17-18, at a time when boys become men. With the transition comes expectation, responsibility and temptation, it’s a world much more complex than just kicking a ball around.

I was too young to recognise that I wasn’t prepared. I wasn’t studying and I wasn’t learning a trade. I wasn’t cultivating an identity that wasn’t entirely fixed around football. I wasn’t filling in the time around training and matches productively. When I signed that first pro contract with the Central Coast Mariners, I thought I’d made it.

In terms of psychology and mental health there’s a lot of arrested development around this point in in a young man’s career. You have to be a more robust and resilient 16-year-old than most of your peers, but it’s all-too easy to plateau, thinking that who you are at that point is enough, instead of continuing to grow and investing in yourself.

There were people around me trying to show me the right path but there was also an expectation that you figured things out for yourself. I knew that I was heading down the wrong path but while my football was keeping me afloat, I thought I could get away with it. It was at this point in my career that I was handed a life changing opportunity in the Championship which was the catalyst of my own destruction. This was when I needed more direction than ever.

The bad habits and poor choices repeated in England, but on a whole other scale. I was playing with guys that had been earning tens of thousands of pounds a month for years who could afford to go out and party and gamble at the casino. I was a 19-year-old trying to keep up, desperate to fit in.

I thought what I was doing was normal, living the life of a footballer in England, especially while I was still training with the first team and captaining the reserves. I wasn’t worried about anything catching up with me because the next contract was always around the corner. Until it wasn’t. At the end of my two-year deal I wasn’t re-signed, quite simply, because I was partying too much.

My family was back home in Sydney, and I was hiding the truth from them and everyone else around me. They saw what I wanted them to see of me, training, playing, keeping up a façade when really, I was on a path of self-destruction. I never signed with an agent who could pull me in and steer me on the right track, maybe this is something I regret, could they have helped? Or would I have just lied to them too. Month after month it was the same story, I’d be broke.

Somehow, I managed to survive like this in Sheffield, but Airdrie is where it all came unstuck. £200 per week in wages. Training just three nights a week. Isolated from friends and family. I had nothing constructive to do, so I spent my days drinking or sleeping. When I could afford too, I’d be in the pub from lunchtime. When I couldn’t I’d stay at home then I’d eventually call my parents for some money… only to start drinking again. You don’t need to be a mental health professional to see the red flags here.

What might seem hard to believe is that this all felt normal to me at the time. This was my experience of life as a professional footballer and I had nothing to measure it against, I knew no better. Deep down I knew I should have been working harder but I was young and I didn’t know how to interrupt the downward spiral.

This is when the depression hit me. Hard. The game I loved, didn’t bring me joy anymore. The one thing that had forever given me my purpose and my identity, I simply no longer wanted to play. What should have been the best year of my life, quickly turned into the worst. Of course, at the time this is not something I recognised and it has taken me a years to come to terms with it all, but this is what the industry is lacking so desperately. Young men that need help during times they don’t even know that they need it. Maybe if I had someone there to help me through these dark days my career and my life would have been completely different.

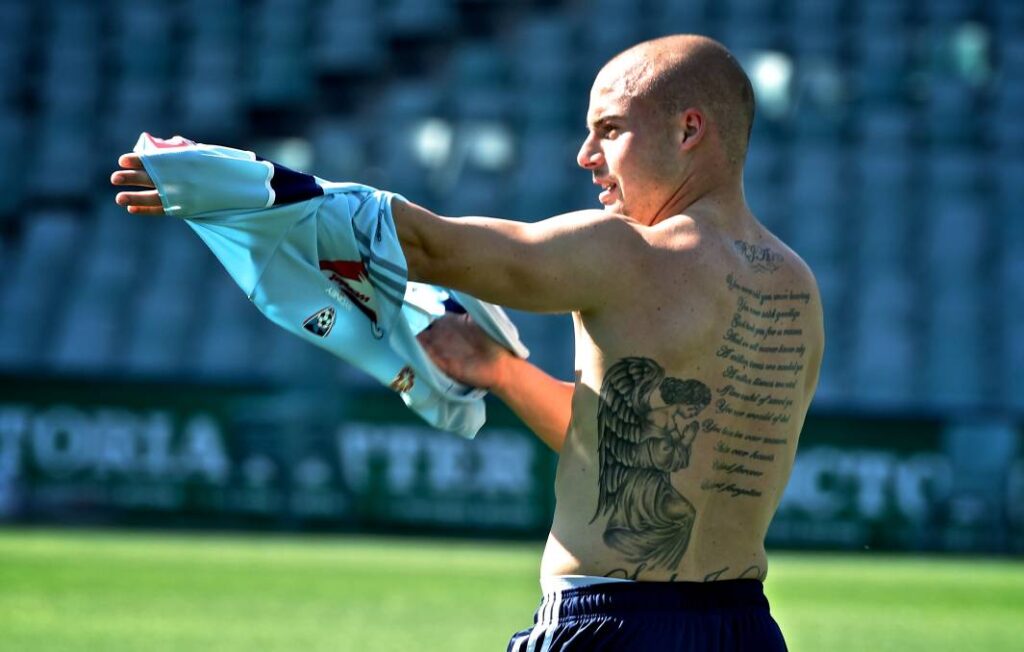

Looking back there were two wake-up calls I naively missed. The first; leaving Sheffield, the second when Sydney FC offered me a route home from Scotland. It actually did the opposite; coming home meant being surrounded by mates and a false sense of belonging to a social status protruded on me from people who didn’t really care about me. I was lured to a life of drinking and partying again which led me to another deep hole.

This time I couldn’t play my way out of trouble. As a kid, going out and drinking took a long time to affect my training and performances, especially when it was part of the culture. I joined Sydney FC as a fit 21-year-old, with a decent reputation after playing in Europe. I played just eight games, in one of which I was sent off. I wasn’t good enough. My athleticism had gone. I didn’t deserve another contract.

The jig was up, my football career seemed over. I spent the next two years working in a warehouse. People would ask me “how’s football?” and I’d tell them I wasn’t playing any more, subconsciously this had an enormous effect on my mental health forcing me to fall deeper into the whole I had dug myself. My identity was shattered. If I wasn’t a footballer, who was I?

I didn’t realise at that time that defining myself as a footballer was part of the problem. You have to be able to identify yourself as a person first and foremost, who you are, your morals, what you believe in, what you stand for before identifying yourself as a footballer. Playing football can only ever be a component of who you are. Otherwise, an injury or a loss of form, can ruin everything including your mental health.

Getting out of that hole was the hardest thing I’ve ever done. I went to some very dark places. But with the help of my partner at the time I regained my motivation and realised that enough was enough. Thankfully Kenny Lowe took my call and invited me to Perth Glory for a trial, which led to a contract.

That was an emotional moment for me. For the first time it hit home. I’d gone from not caring about anything, with nothing to fall back on, no trade, no degree – to this miracle of a second chance, a fresh start, away from Sydney. It felt different. It felt right.

I behaved like a professional footballer for the first time in my career. I worked my way into the first team, played in the FFA Cup final, and started an elimination final. My second season at Glory was tougher but I did enough to get an extra year on my deal. Everything was coming together. I was the best footballer-athlete I’d ever been. Happy ever after, right? Not so fast.

Four days before the start of the 2017-18 season I injured my ankle, rupturing my peroneal retinaculum. The recovery time was measured in months, not weeks. I felt like someone was having a joke, all my hard work, dedication and commitment to becoming a better person, a better player was all slipping through my fingers and there was nothing I could do about it. I thought I’d figured it out but all I’d really done was cover my problems with a band-aid. I was still defined by football. I still didn’t exist outside the game. I still had bad habits. Bad habits that left unchecked, would eventually bring me down.

My biggest fear became a reality. During my recovery I was home all day while my partner was working. I started filling the time by drinking, again, this time only worse. Days turned into weeks; weeks turned into months.

My rehab was a disaster. I didn’t heal properly from the surgery. My muscles weren’t recovering as they should and after six months, I returned half the player I was with a fraction of the mental strength. That downward spiral returned with a vengeance.

My club turned a blind eye to everything that was happening, at a time when I needed them the most. Not just physically but emotionally. I was a shell of the man I wanted to be; this would be the darkest time in my life.

Then the PFA stepped in and saved my life.

They put a protective and supportive arm around me. I want to name a few names here – Beau Busch, Richard Garcia, Dino Djulbic, Rhys Williams – leaders, who listened, understood, and gave me the strength to talk. I was introduced to a psychologist who encouraged me to open up, especially to my family, who I can’t thank enough for their patience and unconditional love.

It’s difficult to put into words the impact speaking to my mum and dad had. It was profound. While I thought they were completely oblivious to my struggles and situation, when I mustered up the courage to talk to them, mum revealed to me they could tell something was wrong. But they didn’t judge me or pressure me and let me own my situation. I felt vulnerable at first, but it just empowered me to seek more support and help. They helped me open and up and see the light during some dark days.

Opening up and seeking help was when the healing process begin. The catharsis of therapy is something else. Spilling your guts to someone, telling them everything, sharing things you’ve kept bottled up for years has an unbelievable ability to relieve pressure. You talk and talk and then things start to click. You understand yourself with so much more clarity. You can feel the weight lifting from your shoulders.

The hardest part for me was coming to terms with the fact that I was the person that had done so many things I regretted. But that stage is critical. You have to confront what you’ve done, the decisions you’ve made. You have to accept your decisions and own them – good or bad – they’re all part of who you are and until you address that you’ll never fully understand yourself.

One thing I realised on my journey was that maybe football wasn’t for me. Maybe it never was? I’m happier and healthier now than I was living large, being recognised, and earning a reputation. What I do believe now is that everything happens for a reason and life teaches you lessons that at the time you don’t recognise.

It’s taken two years in total to go from where I was, to being comfortable sharing my experience. Two years adjusting to living day by day, staying present, appreciating what I have and what’s around me instead of worrying about what could have been, holding myself to some impossible standard. If you accept who you are at each given moment, life is a lot more satisfying.

That’s not to disregard ambition, but it’s about putting those expectations into context.

I now know that I need to remain occupied at all times. I cannot allow my mind to be more active than my body, this what my new career in Real Estate has allowed me to discover. Having a purpose, being present, staying busy, helping people and not allowing distractions to pull me back down.

This is all accompanied by learning better how to deal with difficult situations. Everyone has their own techniques. One of mine is to count to ten in a certain rhythm that refocuses my attention and brings me back into the moment. I now know my limits, my triggers and how to cope with them. It sounds simple but it’s life-changing. Not just the act in itself of walking away from a situation that could have negative consequences, but what it represents about who I am and how far I’ve come. I used to be defined by being the guy that was always at the pub, the life of the party or out with friends. My identity was warped into thinking I had to be the life and soul of the party. I now know that this is all superficial and life has so many more important things to offer that aren’t connected to a social status or a title.

My perspective on life has changed dramatically over the last few years, I have a passion for helping those like me who can be so easily succumb to a false sense of fame and struggle with mental health issues in secret, generally brought on by your own poor choices.

What the PFA did for me still gives me goosebumps. It’s time for me to give something back.

PFA Wellbeing Services

PFA Members have access to a variety of wellbeing programs and services designed to provide critical support in times of need but also to assist them in dealing with the demands of professional sport both on and off the pitch. PFA Members can access confidential counselling and psychological support services to assist in dealing with a variety of challenges they may be facing, including: addiction, anxiety, depression, relationship breakdown, grief and transition.

To access the PFA’s counselling or psychological services please contact your Player Development Manager.

In addition, members can contact Lifeline 13 11 14 for crisis support 24 hours a day.