The big question in Australian football is how best to bottle the magic generated by the Women’s World Cup.

The obvious place to channel the newfound fervour is the A-League Women (ALW) competition. The Matildas – always ahead of the curve – asked fans to get around the ALW in their pre-World Cup video.

This call-to-action has become widespread and, encouragingly, there are reports of record demand for ALW memberships ahead of the new season starting in October.

A thriving ALW will provide the high-quality careers our players deserve, a new asset for brands and broadcasters, and a pipeline for future World Cup stars. In a broader cultural sense, it can carry on the work of the World Cup of making women athletes more visible and inspiring girls across Australia and New Zealand.

For governments, commercial partners, and the APL and clubs themselves, the question is how big this thing can get and how soon?

A useful reference, and the focus of this PFA Post, is England’s Women’s Super League (WSL), which is a few years further down the road from where the ALW is now. It has been on a staggering growth trajectory and is now one of, if not the world’s leading women’s domestic leagues.

Of course, there are differences in the English and Australian football landscapes, so progress will not be identical in both countries. But there are still valuable lessons to extract from the experience of a competition which developed the Lionesses team which ended the Matildas’ dream World Cup run.

A short history: from full-time professionalism to four-fold growth

The WSL was established in 2010, two years after the ALW. It underwent a series of format changes before the Football Association’s 2017 ‘Gameplan for Growth’ kickstarted the current era of rapid progress.

The strategy document targeted a doubling of female participation, and doubling of attendances for the WSL and Lionesses matches, by 2020. It achieved all three goals (WSL attendances actually tripled by 2020).

In 2018-19, the WSL took the bold step of going full-time professional. Clubs had to reapply for admission under strict new licensing requirements, which led to a controversial shake-up in the make-up of the league. Some longstanding clubs were replaced by others that were more willing or able to invest.

The relaunched competition soon attracted ground-breaking investments from forward-thinking partners. In 2019, Barclays came on as naming-rights sponsor for more than £10m over three seasons, including £500k for prize money. The bank renewed the deal last year for another three seasons at a reported £30m. In 2021, the broadcast rights were sold to Sky Sports and BBC for £8m per season. One quarter of this revenue is distributed to the second tier Women’s Championship.

Combined club revenues have grown from £8.5m in 2018 to £30.7m in 2022 (not including a couple of clubs which do not publish their revenues). Financial statements do not yet cover the 2022-23 season, but this growth is likely to have continued or accelerated off the back of the Lionesses’ home Euros win last year. Average attendances nearly tripled from 2021-22 to 2022-23, up from 1,923 to 5,616. Sky has said its TV audience grew by 70% this past season.

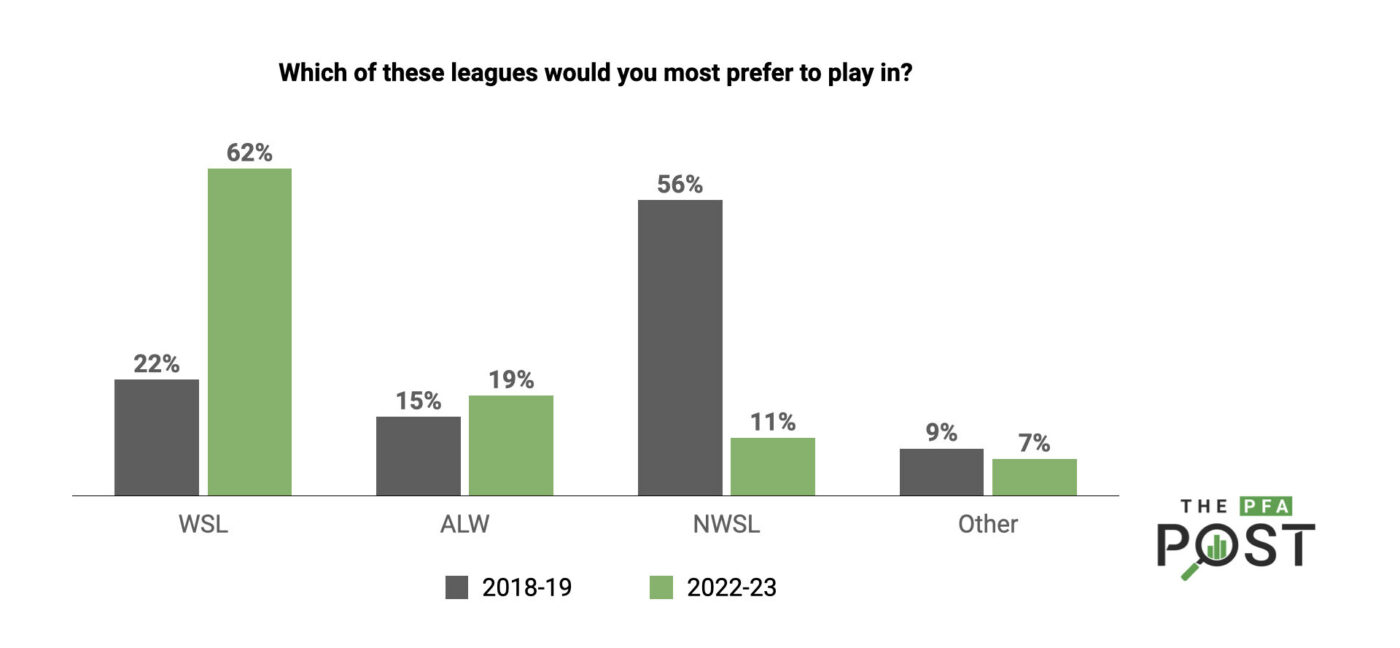

One other way to measure the progress of the league is the perception of players, which the PFA has been tracking over time. In 2018-19, 22% of ALW players surveyed chose the WSL as their most preferred domestic league; in 2022-23, this was 62%.

Where to next for WSL?

UK women’s football is not standing still. In July, the British government published the findings of an independent review into women’s football, titled Raising the Bar – Reframing the Opportunity in Women’s Football. Among its progressive and ambitious recommendations was for the women’s second tier – the Championship – to follow the WSL’s lead and provide full-time professionalism.

The chair of the review, former England international Karen Carney, believes women’s football in the UK could be a billion-pound industry by 2033.

Leading vs lagging investment

The rapid progress described above is a lesson in ‘leading’ investment in women’s football. The Football Association, Barclays, the broadcasters, and clubs took a ‘build it and they will come’ approach, enhancing the product in the belief that fan interest would follow.

This is key, because there is a tendency for investment in women’s football to ‘lag’ rather than ‘lead’. That is, it seems that the players always have to prove their worth first, before the money catches up.

This ‘lag’ logic is flawed for two reasons. Firstly, it’s hard to think of an example when, with hindsight, a serious investment into women’s football hasn’t been (quickly) justified, such is the industry’s potential and demonstrated growth. Secondly, the investment in women’s potential becomes self-fulfilling, because better-resourced players will create a more compelling product.

World Cup prize money is a classic example. FIFA has effectively said that players must fill the stadia and attract the eyeballs before they can be paid the same as men. As always, the women have now cleared this bar despite the relative lack of investment. If FIFA had levelled the playing field four, eight, or 12 years ago, we could have been here sooner. FIFA’s go-slow has denied itself the opportunity to create a commercial behemoth, while denying any outgoing players the equal treatment future generations might finally enjoy.

By contrast, Barclays’ head of sponsorship partnerships, Katy Bowman, recently reflected on the brand’s decision to be an early adopter in 2019 and then triple down last year.

“You’re still buying into what could be because it’s still not there yet. You’re buying into a promise of growth from a commercial standpoint, for sure. In terms of monetary, I don’t know how difficult that conversation was, but it was never about what return on investment this is going to be. It’s a bit of a no-brainer. We know it will grow and the ambition will be for it to grow. But we know we also need to help it. It’s a journey, so you get out what you put in.”

This theme echoes through the Matildas’ recent journey. In 2019, the first gender-equal National Teams Collective Bargaining Agreement felt bold and progressive. Looking back now, it is unthinkable that the Matildas wouldn’t have been afforded the same world class standards as the Socceroos to maximise their nation-changing World Cup performances. And partly because of that leading investment in them, the Matildas are suddenly a commercial engine on par with the men’s team, delivering a swift and considerable return for Football Australia, brands, and broadcasters.

The smart money bets on where women’s football will be in four years.

The opportunity: players fully focused on football

Investment itself does not guarantee increased support. It’s what that investment enables.

In the case of the WSL, the past five years represent a virtuous cycle of increased investment improving standards, improved standards attracting more fans, more fans begetting more investment, and so on.

The sums were significant, but in terms of return on investment, relatively modest injections had transformative power.

This is because the starting point was a league where players could not commit fully to their craft. The shift to full-time careers enabled players to quickly level up, producing a more compelling product. Subsequent increases to player payments, which have risen rapidly in line with club revenues, have attracted top global talent to the league and driven competitive tensions which incentivise success and further raise performance levels.

This path lies in front of the ALW. Three in five of its players currently work a second job outside of football, and around half of those spend more than 20 hours a week in their other employment. The lesson from the WSL is that alleviating players of this burden will be a step-change towards fulfilling the competition’s potential for all stakeholders.

Australian fans have voted with their feet and shown that they will watch high-level women’s football. It’s a no-brainer to ensure our A-League Women players can meet their newfound interest in our sport with the best possible versions of themselves.

The challenge: without mega-clubs, all stakeholders must step up

The biggest difference between the WSL and the ALW is that the economic scale of the men’s game in England dwarfs that in Australia.

Women’s football has the capacity to be a standalone enterprise, but it would be remiss to draw a comparison between the competitions without acknowledging the context in which the WSL has thrived.

The reality is that WSL teams sit under club umbrellas of the world’s richest football brands, which have the capacity to invest in women’s football at a fraction of their overall budget.

In 2021-22, Arsenal Women’s expenses were 1.6% of their men’s team budget, while Manchester United Women’s were 0.7%. The WSL clubs with men’s teams in England’s second tier, Reading and Birmingham, had slightly smaller gaps between their teams because their men’s costs were less exorbitant.

The scale of fandom for the men’s teams is also relevant. Arsenal Women played three league matches at the Emirates Stadium in 2022-23, attracting more than 40,000 fans each time. This dragged their season average up from 3,544 in 2021-22 to 16,976 last season, more than any A-League Men’s team. This quantum leap would likely not have been possible without the pre-existing support for the Arsenal brand on the men’s side.

However, these are differences in scale, not kind. Most ALW teams are also embedded in larger dual-team clubs with everything to gain from an explosion of interest in women’s football. We too have access to larger venues where appropriate and extant football, media, and commercial personnel and infrastructure to assist with rapid upscaling. There are no hard capacity limits.

Arguably, the ALW presents a relatively greater opportunity for Australian clubs than English ones, because, with respect, our women’s teams are much closer to world football’s summit than our men’s.

ALW clubs can point to the development of every Matilda in the squad which just finished fourth in the world. With the right investment, it can credibly offer fans the opportunity to buy in to the journeys of the next generation of world-beaters. Without the right investment, this narrative may be a mirage.

Without global mega-clubs to fall back on, other stakeholders must lead the push in Australia. Government, commercial partners, and broadcasters share the power to drive our own transformative era, if they have the vision to see what’s possible.