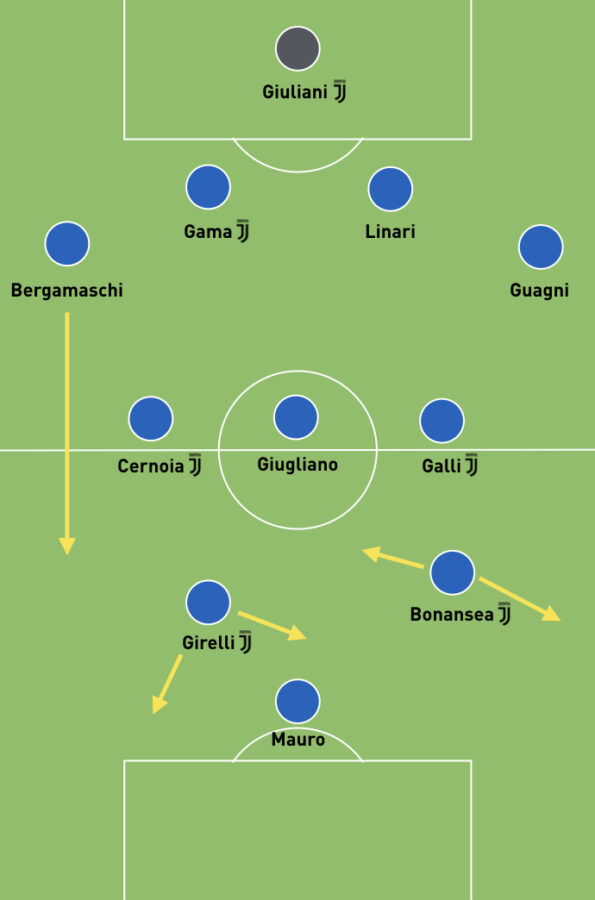

Italy coach Milena Bertolini found success with a lopsided 4-3-3 formation during World Cup qualifying, winning their first seven matches with 18 goals scored and 2 conceded, before losing a dead rubber 2-1 to Belgium in the final game.

The shape she uses features Cristiana Girelli, top scorer in qualifying, playing just off a central striker. On the left side, Italy’s outstanding individual attacker Barbara Bonansea usually starts in a more natural winger position, making the shape resemble a 4-4-2 at times, but she also roams between the lines and often switches to the right flank. The result is a fluid attacking trident with a narrow shape and width provided by fullbacks on the overlap.

At the back, injury rules out key centre back Cecilia Salvai, while the fullback spots feature the least predictable selections due to competition from Elisa Bartoli and Lisa Boattin.

Even though Italy are considered third favourites in our group, there are two reasons to believe the Azzurre could outperform their rank going into the World Cup. The first is form: the team is unbeaten in nine matches in 2019, only losing the final of the Cyprus Cup to North Korea only on penalties. The second is familiarity: as denoted on the graphic, more than half the likely starting XI all play club football with Juventus, which has won the league title in Italy in both its first two seasons.

ATTACK

Italy have an unstructured approach to possession, but a potent one. The fullbacks get forward, the midfield three all make forward runs at different times and Bonansea has a free role, so it can be hard for defenders to know where to look.

Overlapping fullbacks with plenty of targets

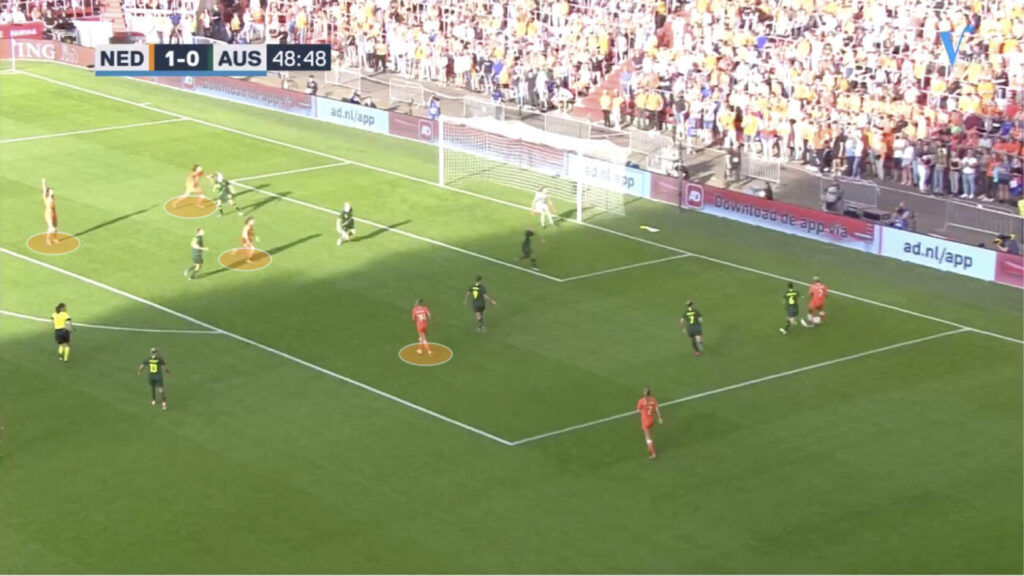

When the fullbacks get forward on the overlap, Italy invariably have good numbers in the box to attack the cross, with three front three joined by at least one midfield runner.

These situations will likely be in sharp focus for the Matildas this week, after conceding from a similar situation against the Netherlands on the weekend.

Forward runs out of midfield

Unlike in most modern 4-3-3 formations, none of Italy’s midfielders are instructed to play a holding role. This freedom causes problems for them in transition moments, which we’ll get to later, but the forward runs from Valentina Cernoia, Manuela Giugliano and Aurora Galli have the capacity to surprise a defence which is already preoccupied with three attackers who roam in central areas.

The movement is not random but well-coordinated. In these examples you’ll see a striker coming short or moving sideways to drag her marker out of position while a midfielder makes the run into the vacated space.

From these examples it’s clear that Cernoia is the team’s best creator from the deeper positions, cutting inside on her left foot to deliver a range of short and long passes.

Individual threat

But the key weapons are undoubtedly Bonansea and Girelli. Bonansea has been Juve’s top scorer in both seasons, and her constant desire to cut onto her right foot and run with the ball is completely predictable but no less effective for it.

DEFENDING

Space between defence and midfield

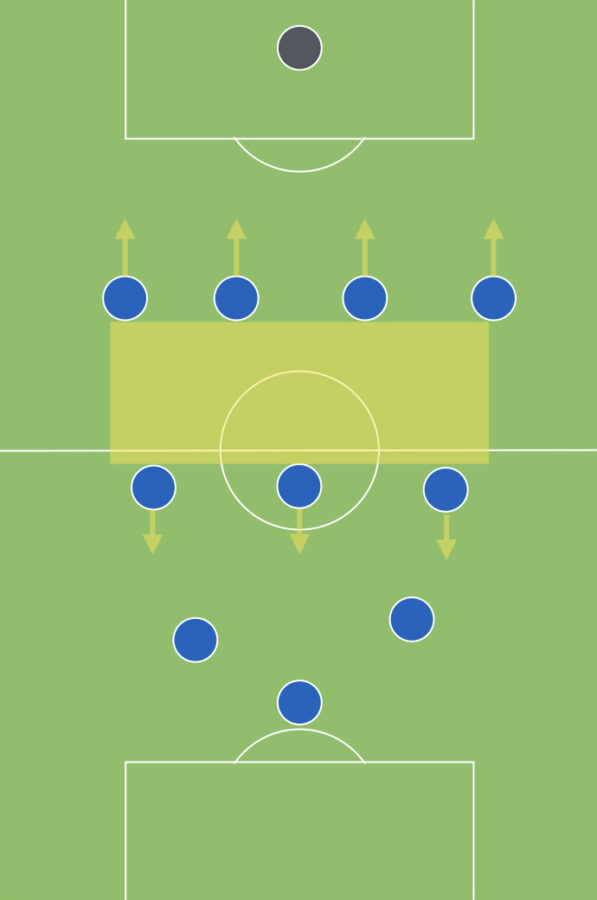

We’ll focus on one key area the Matildas may be able to exploit. Italy’s unusual flat midfield three gives them something different going forward, but it also leaves space in front of the centre backs. The midfield three are drawn forward to press players in front of them, while the back four tends to drop deep, so a hole is created between the two units. This occurs both during transition moments and in structured situations.

The examples here show moments which could be exploited, if Australia can get players between the lines and play through these areas quicker than Italy’s recent opponents were able to. So the clips show the opportunity that exists, rather than the template to replicate.

Structure: Narrow high press

In these examples we see that Italy’s front three press high in a narrow spearhead, while the midfield squeezes up behind in a narrow, flat line of three. This leaves space down the sides, so a simple ball out the fullback opens up a diagonal ball into the number ten position.

Even on Italy’s defensive goal kick, Ireland’s playmaker can easily get on the ball facing forward in this space between the lines.

Transition: Back door left open

During build up, none of Italy’s midfielders are instructed to hold their position in the six role, so moments occur when they lose possession with all midfielders ahead of the ball. This is compounded by the fact their fullbacks take up high positions during structured possession, leaving the centre backs exposed both in front and down the sides.

SET PIECES

Defensive weakness on corners – at both ends?

Italy have conceded an inordinate number of goals from defensive set pieces recently. For defensive corners, they use a zonal system with all players back. But as Switzerland and North Korea (twice) exposed, the back post area has proved to be vulnerable to runners coming from deep.

If the opposition sends a second player out for a short corner, Italy end up with the edge of the box completely exposed, which could lead to trouble if any balls fell to this area.

On attacking corners, Italy are ultra-attacking, with a short option and six players in the box, being one on the keeper and the other five arriving in line with the flight of the ball along the six-yard box.

This only leaves two outfield players to stay back near halfway. The edge of the box is once again left free. For the Matildas, defending the corner is the first priority, but launching counterattacks from defensive set pieces is an increasingly important aspect of a modern game when space is otherwise at a premium, and Australia has the pace to profit from this scenario if an initial clearance can be latched onto.