Norway play a classic Scandinavian 4-4-2 with a focus on defensive organisation. They possess individual quality to rival the Matildas but their star player is arguably their team work ethic.

They have been extremely stable this tournament, with nine players starting all three group matches. Their only variation has been to deploy their #10, Caroline Graham Hansen, in the right midfield role at moments when they have needed to press for goals, thus allowing a second striker to join key goal-getter Isabell Herslovsen. Against a tougher opponent like Australia, as with France, Martin Sjögren is likely to again call on workhorse winger Karina Sævik to bolster the right side of the midfield four.

The shape of Norway’s attack is dependent on Hansen’s fitness. The rising star is under an injury cloud after having her left ankle crunched in the course of winning her side’s second penalty against South Korea. If she is not fit to line up just behind Hersloven, Lisa-Marie Utland will instead form more of an out-and-out front two, making for a more direct but less creative threat for the Matildas to deal with.

DEFENCE

Pressing trap awaits

It makes sense to start with Norway’s stronger phase of play, which is when their opponent has the ball. They form a compact and well-organised 4-4-2 medium block. They tend to leave the pass to the fullback open, forcing their opponent to one side then springing a pressing trap.

While this is a common strategy in modern football, what’s impressive about Norway’s execution is that their players have been drilled with the defensive triple threat: work-rate, positioning, and individual behaviours.

The strikers and wingers on the far side to the ball are totally alert and perfectly positioned. All players are very aware of cutting out lines of pass, managing distances between opponents, and timing their aggressive pressing runs. This allows them to steal the ball in good positions from which to launch rapid counterattacks.

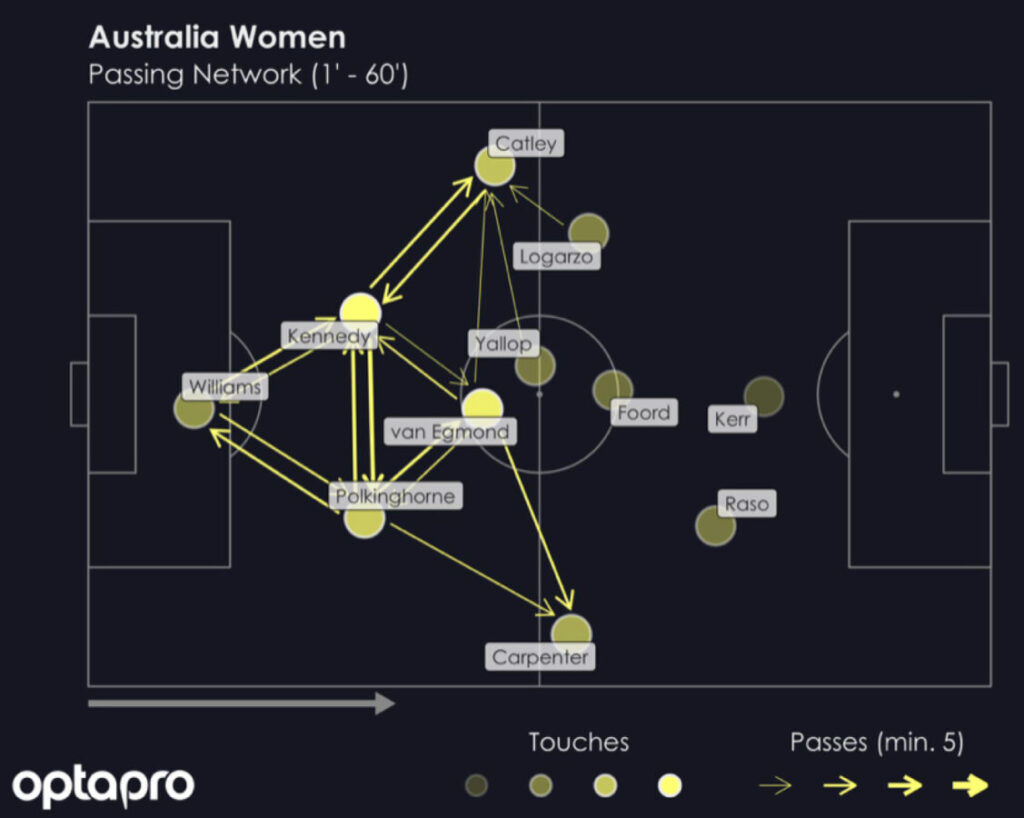

When we observe Australia’s passing network against Italy (which looked similar in each match), we see that the Matildas’ dominance of possession has not yet translated into fluid movement of the ball through the thirds, but rather has been mostly comprised of circulation across the back four and #6.

The clash between the Matildas’ evolving possession game, which is Ante Milicic’s main focus, and Norway’s defensive strength, could be the decisive tactical battleground of this match.

Back third on lockdown

When opponents do progress to Norway’s back third, the Grasshoppers defend their penalty area better than most sides at this tournament. They work back in numbers, keeping their two banks of four intact.

Maria Thorisdottir’s defensive game is world class. She and her central defensive partner Maren Mjelde both play for Chelsea, so their understanding is tight.

Watch in the clips how midfield players mark tightly and track runs, double back in wide areas, protect the edge of the box from shots and fill in for the back four when required.

ATTACK

Vertical build-up with pros and cons

In his preview for the Guardian, Richard Parkin notes that Norway’s six group goals included two penalties, two own goals, and a deflected effort from a corner. The data bears this out. According to Opta’s expected goals model, excluding own goals and penalties, Norway racked up just 0.62, 0.23 and 0.59 in their respective games.

All this is to say is that creating chances is not the team’s strength, which why they may actually be at their most dangerous when the Matildas have the ball.

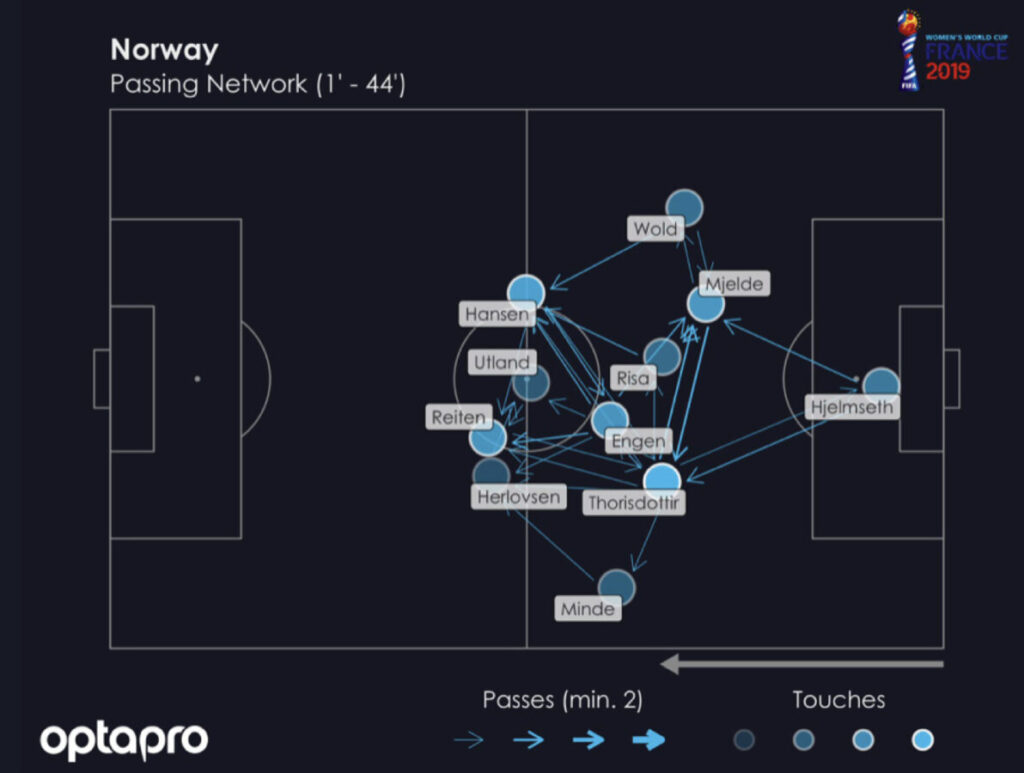

Their shape in possession is clearly visible in this OptaPro passing graphic from the South Korea match and the screenshot against France. The fullbacks push very high and the wide midfielders move inside between the lines, overloading the central zone. At their best, this allows them to break the opponent’s lines with a series of vertical passes, bringing their fullbacks into play as width in the final third.

But this structure has a flipside. The fullbacks start too high and wide for the centre backs to be able to pass to them directly (or if those passes are attempted, the opposing winger can pick them off). So, if pressed, the defenders can be forced into errors or aimless long balls.

Final third: Overload between the lines

Higher up the pitch, Norway’s high fullbacks and narrow midfield structure gives them up to three players between the opposition midfield and defence. They dribble and pass through this area and look to slip balls through for the striker, who drifts all across the backline looking for the moment to run off the shoulder of a defender and get in behind.