The PFA’s 2022-23 A-League Women (ALW) player survey has revealed the strain placed on players as the league transitions through an awkward phase on the path to full-time professionalism.

As the league develops, the demands on players are increasing, but the careers provided are not yet sufficient for most players to support themselves solely through football.

This means many players are caught in a stressful tug-of-war between growing football commitments (which they embrace) and other work, which remains necessary until the competition can provide a full-time, year-round employment framework.

The answer is certainly not to go backwards. The players have fought for the progress embodied by improved standards, increased payments, and more teams and matches. They welcome the greater expectations put on them as a result.

The PFA also recognises that 12-month contracts for ALW players and staff are a priority goal for the Australian Professional Leagues (APL).

So, while the survey findings highlight a negative side effect of that progress at this juncture in the competition’s development, the only remedy is to push through as quickly as possible to a milestone when players can afford to focus solely on football, should they choose to.

The benefit to players will be relief from the tension they are currently reporting, and the benefit to the broader game from unlocking the potential of an uncompromised development environment may be even greater.

Majority of players still need to work outside football

Under the 2021-2026 A-Leagues Collective Bargaining Agreement (CBA), the ALW minimum retainer was $20,608 in 2022-23, for a 29-week contract. Most players earned at or close to the minimum this past season.

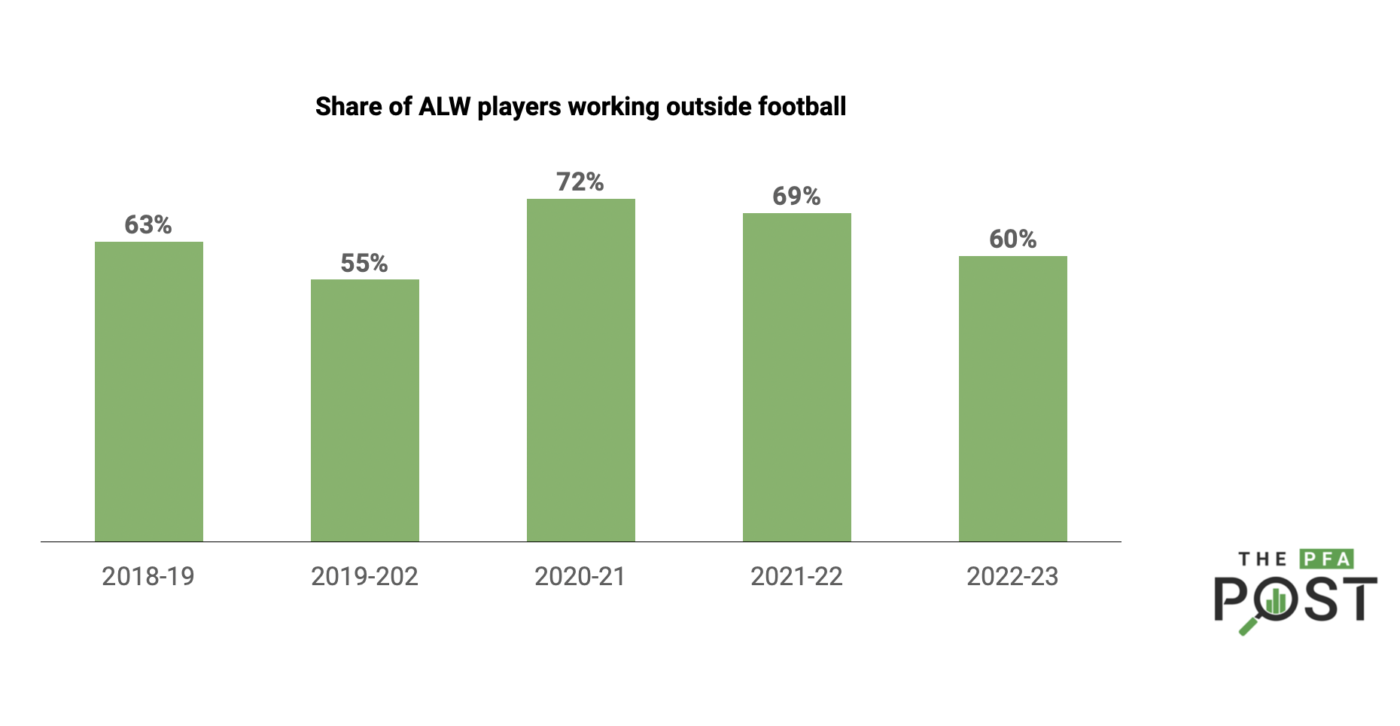

At this remuneration, it is obvious why many players still need to take on other work to get by. This season, three in five ALW players worked outside football. This rose as high as 72% during the pandemic.

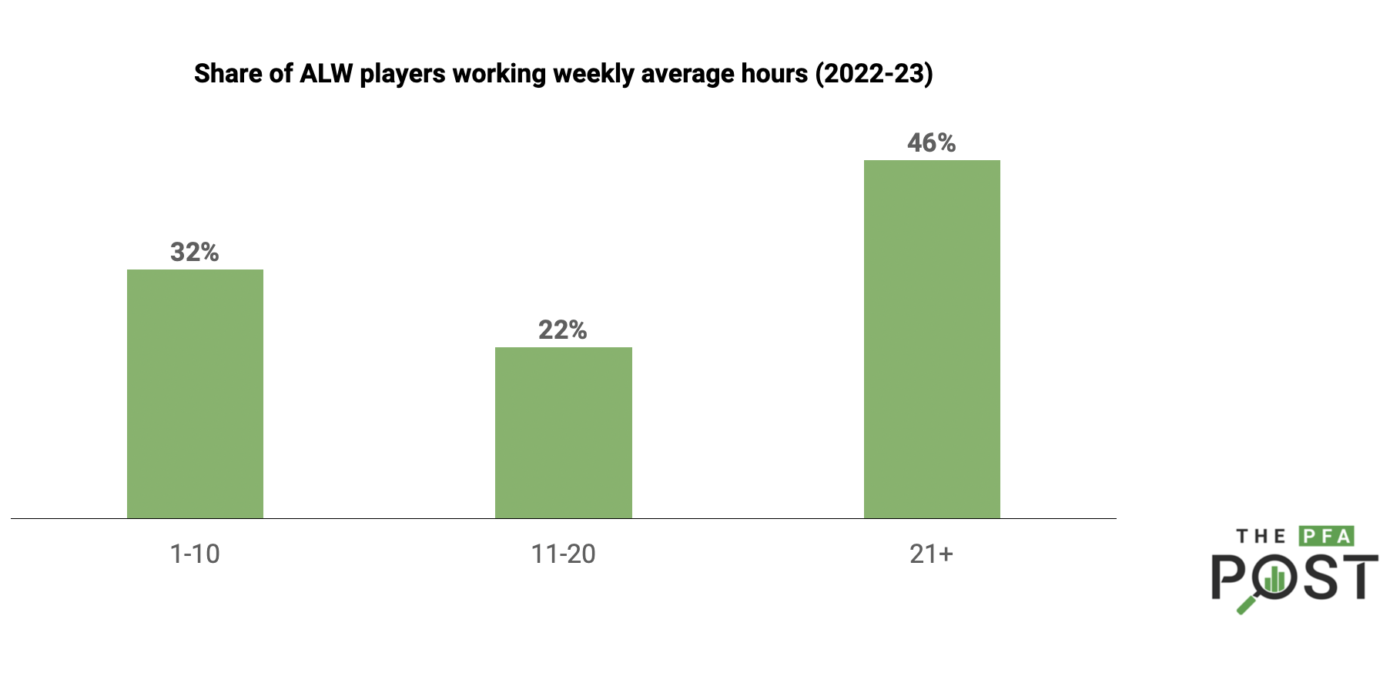

Nearly half (46%) of those who worked this season put in more than 20 hours at their other job/s in the average week.

In addition, 43% of the players who were working were also studying in some form.

By contrast, only 15% of A-League Men players were doing some work outside of playing this season, and 93% of those worked less than ten hours per week.

The problem: declining sense of balance despite (because of?) league evolution

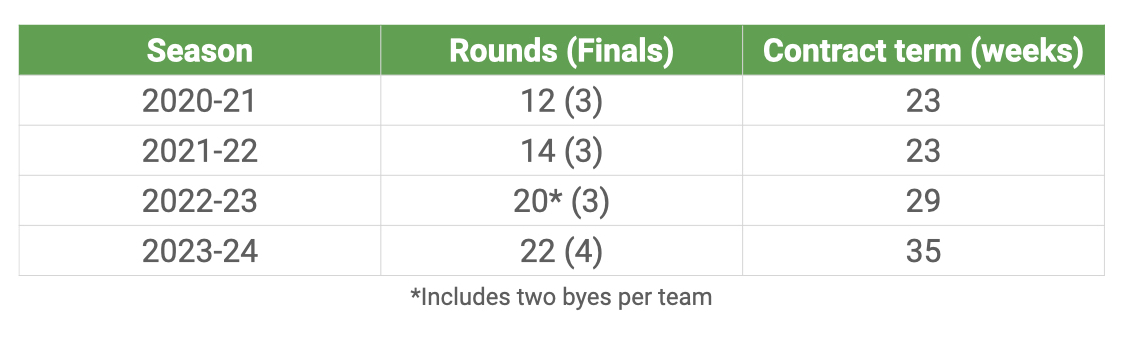

As the season has grown in length, the length of players’ contracts has grown accordingly, as the table below illustrates.

It’s great that the ALW now provides an employment framework for more than half the year, but at the same time, we can acknowledge that the window for other meaningful opportunities has shrunk.

For some players, this might mean it’s getting harder to find work secondments during the off-season. For others, other playing opportunities might be restricted.

To that latter point, the PFA’s 2017-18 ALW Report (p14) highlighted the reciprocal dynamic between the ALW and the United States’ National Women’s Soccer League, with dozens of players able to build a full calendar of elite play across the two due to the “dovetailing” of the two leagues’ season windows at the time. As the report forewarned would be the case, fewer players now tread this path because this dynamic has devolved as both leagues independently expanded.

The number of hours ALW players are supposed to commit to their clubs has remained static at the part-time rate of 20 per week. However, anecdotally, players are reporting that this is more commonly being exceeded.

To round out the increasing demands on ALW players, it could be argued that as the standard of football increases, any given hour is progressively more taxing, although this can’t be quantified.

What we can evidence is the degree to which players feel able to juggle football commitments with work, study, and life generally – because we’ve been asking them this question for the past six years.

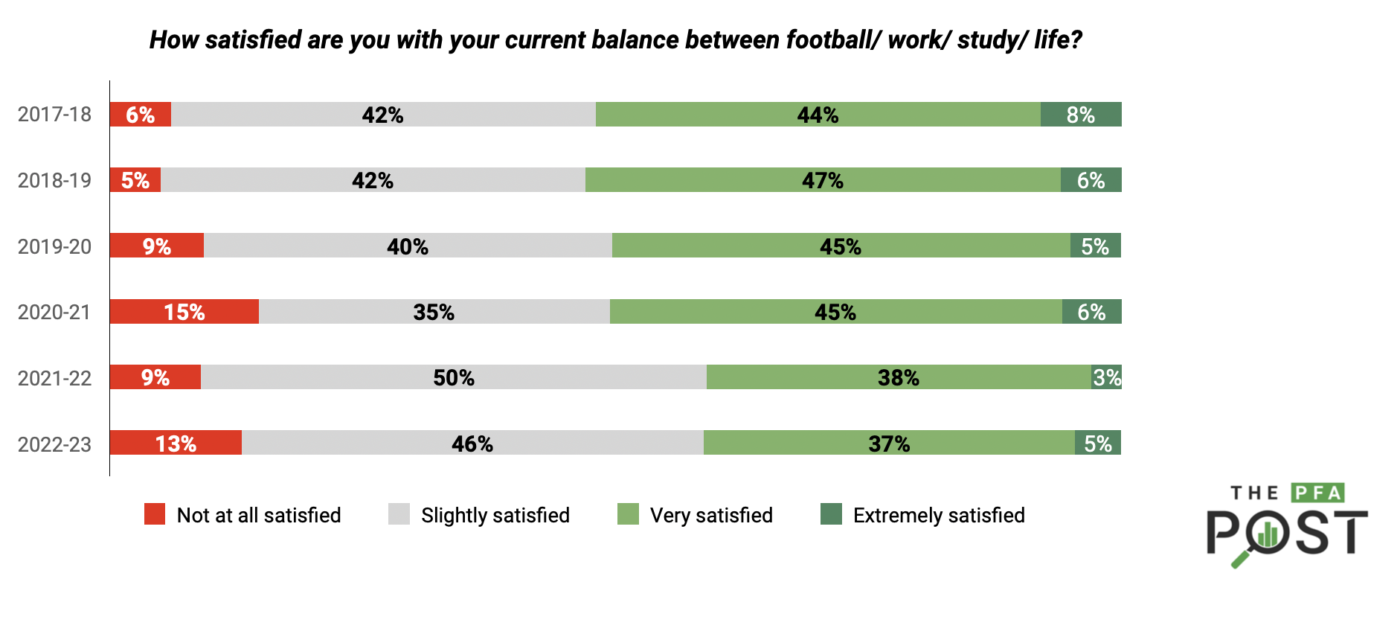

The survey reveals that since 2017-18, the share of players who are satisfied with their life balance has declined.

It’s particularly useful when looking at the chart to compare the most recent two seasons (under the new CBA) to the two earliest seasons, in the pre-COVID normal.

As demands on players increase in the ways described, evidently there is a side effect of more players feeling stretched thin. Nowadays, well more than half are either ‘not at all’ or only ‘slightly’ satisfied with their life balance.

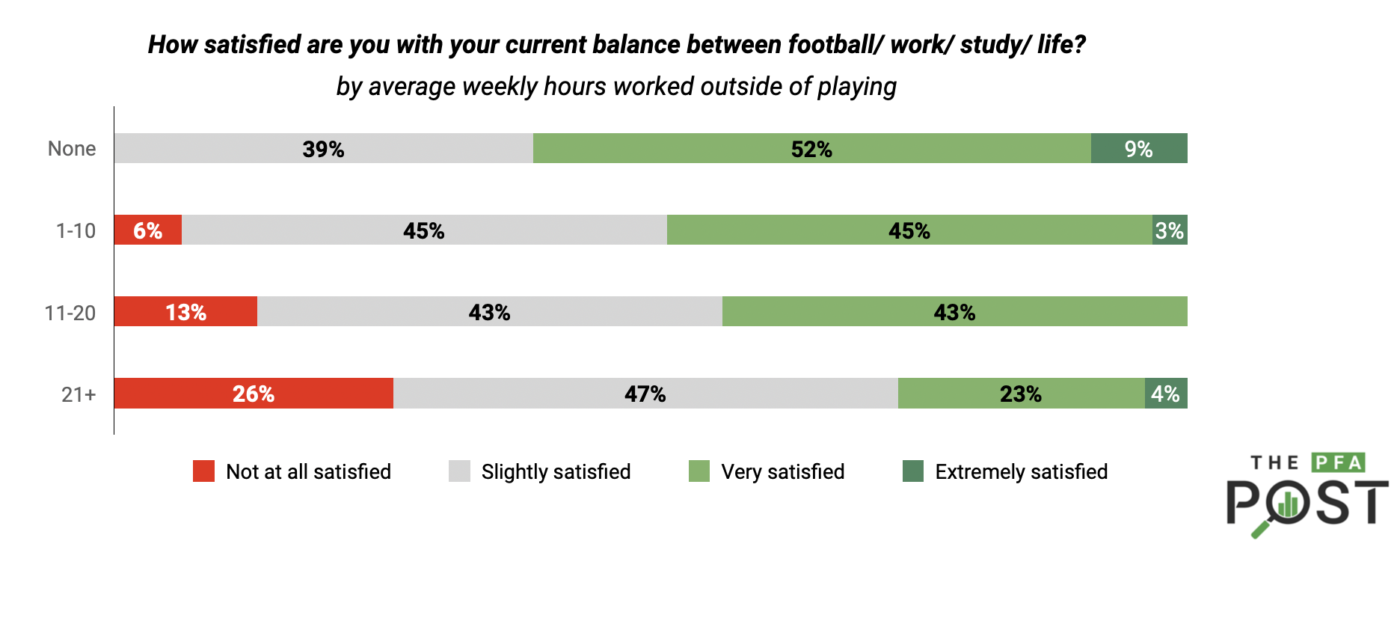

Drilling down into the results from this season, there is one factor that clearly correlates with life-balance satisfaction.

The relationship is clear: more hours worked outside football, less life-balance satisfaction.

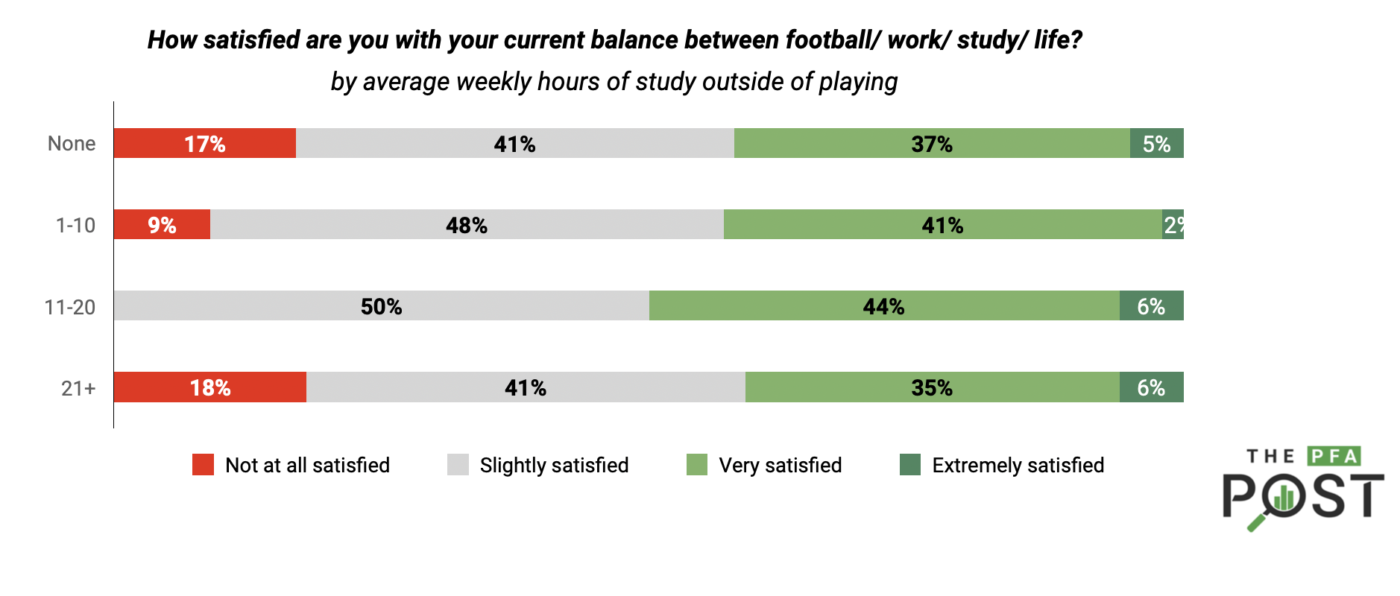

Importantly, this same relationship does not hold when looking at weekly hours of study. In fact, those studying less than 20 hours per week are actually more satisfied than those not studying at all:

So, life-balance dissatisfaction is not about being busy per se, but about players being forced to spend time doing things they don’t want to do, like working.

As we showed earlier, the share of players working has not risen over time, so the recent decrease in life-balance satisfaction across the playing cohort is probably more driven by what’s happening inside clubs.

Survey comments paint a vivid picture of the unsustainable balancing act the players are having to perform to commit to football:

- I don’t want to feel like I have to work between seasons (for example: most of us do not get paid in the off season). It is a lot to juggle, especially going away for national team camps and the immense amount of traveling. I feel this weight on my shoulders from my work obligations.

- If my work and football commitments clash, I am expected by my coach to skip work (where I get paid more and am respected more), and I am expected by my boss to skip soccer, and neither care if you suffer financially or reputation wise for it.

- I feel as though in the next year or two I will have to transition to working in my field (that I studied at uni) and playing at the same time as money from football isn’t sustainable – I am more than happy to do this but I do have concern that coaches may not understand/be happy about this decision. I think until our yearly salary is sustainable programs need to be run considering this. I’m very lucky to have a job and a boss that understands. Unfortunately it means that I make less money but it also means I can do both.

- I work as a casual graduate architect. It’s very beneficial for the mental state while in season, at the same time I would’ve liked to have had more balance given football’s mental and physical demands.

- Only able to work night shifts due to morning trainings so it’s very hard to get adequate sleep after a night shift.

- Club needs to be more understanding of taking leave from work to travel to games and give more notice of if player is travelling or not

Among the 40% of players who did not work outside football, there are more who probably need to earn more money but find the prospect simply unmanageable:

- I just feel like there’s no time for anything else except football. Sometimes I feel tired and burnout enough playing the sport yet alone stressing out about outside commitments. Having to focus on life outside of football and money it has a real impact on mental health.

In the discourse around Australian football’s talent development pathways, a lot of focus is put on the cost of elite programs which might price out some prospects that the game can’t afford to lose. But one comment showed that financial pressure could even block ALW players from fulfilling their potential:

- It is difficult having to work an extra 40 hours a week just to get by, when many of my teammates don’t. This impacts my ability to perform, and takes away from what I am able to put into football, as well as takes away what I’m able to get out of it. It is difficult to compete with teammates who have the resources and ability to give 100% of their time and energy to football.

Solutions: long-term goals and immediate actions

Football is not the only sport facing this issue. The AFLPA has set a goal for full-time professionalism for AFLW players by 2026.

The PFA also acknowledges that this shift won’t happen overnight. The 2021-2026 CBA represents significant progress, building towards a minimum salary of $26,500 in a 35-week contract in its final year (2025-26).

The PFA and APL review the CBA each season to ensure it remains fit for purpose in the context of the rapid development of women’s football. These constructive discussions involve assessing the salary cap, an increase to which will enable more players in each squad to be paid at higher rates. The addition of new teams will afford more players these opportunities.

Delivering full-time pro contracts is ultimately the right thing to do for women athletes, but it should also be seen as an investment, not a cost. Unlike AFLW clubs, ALW clubs can tap into revenue streams such as FIFA’s World Cup Club Benefits and the growing international women’s transfer market, if it houses players of sufficient quality.

A similar frame should be applied to the inception of world class A-League Women academies, which would give Australian girls a pathway to fulfil their potential in the sport, and give Australian football a pipeline of valuable talent.

Without these advancements, the competition risks falling behind. In 2019, Australia’s World Cup squad featured eight domestic-based players; in 2023, this has fallen to two. Meanwhile, the UK Women’s Super League tripled its revenues in the three years after going full-time pro in 2018-19. This provided a platform for the competition to capitalise on England’s successful hosting of the 2022 Women’s Euros: crowds tripled this season and Arsenal Women now attract more fans per game than any A-League Men team.

In the immediate term, the survey reminds clubs that ALW players need to be supported in balancing their competing demands.

The survey revealed that all but three ALW clubs mostly failed to provide players with the required two-month advance training schedule and seven days’ notice of any changes. This CBA provision applies to both the ALM and ALW, but it is arguably most important for the ALW given the need for many players to plan around other work commitments out of financial necessity.

Three out of four (76%) ALW players across the league agreed that at their club, “Players’ lives away from football are supported”. But this fell to 63% among players who were working 21+ hours per week.

Full-time professionalism is an important stretch goal, but there’s more clubs can do right now to ease the path there.