The PFA will soon release a comprehensive report on the Socceroos’ 2022 World Cup campaign, with a focus on the policy implications of the tournament for Australian football.

Topics will include the players’ experiences in camp, the impact of the tournament on the Australian football economy, scheduling and workload, the pandemic’s impact on the qualifying campaign, and the players’ attitudes towards emerging issues, captured through an exclusive post-tournament survey. Some of the survey results are included towards the end of this article.

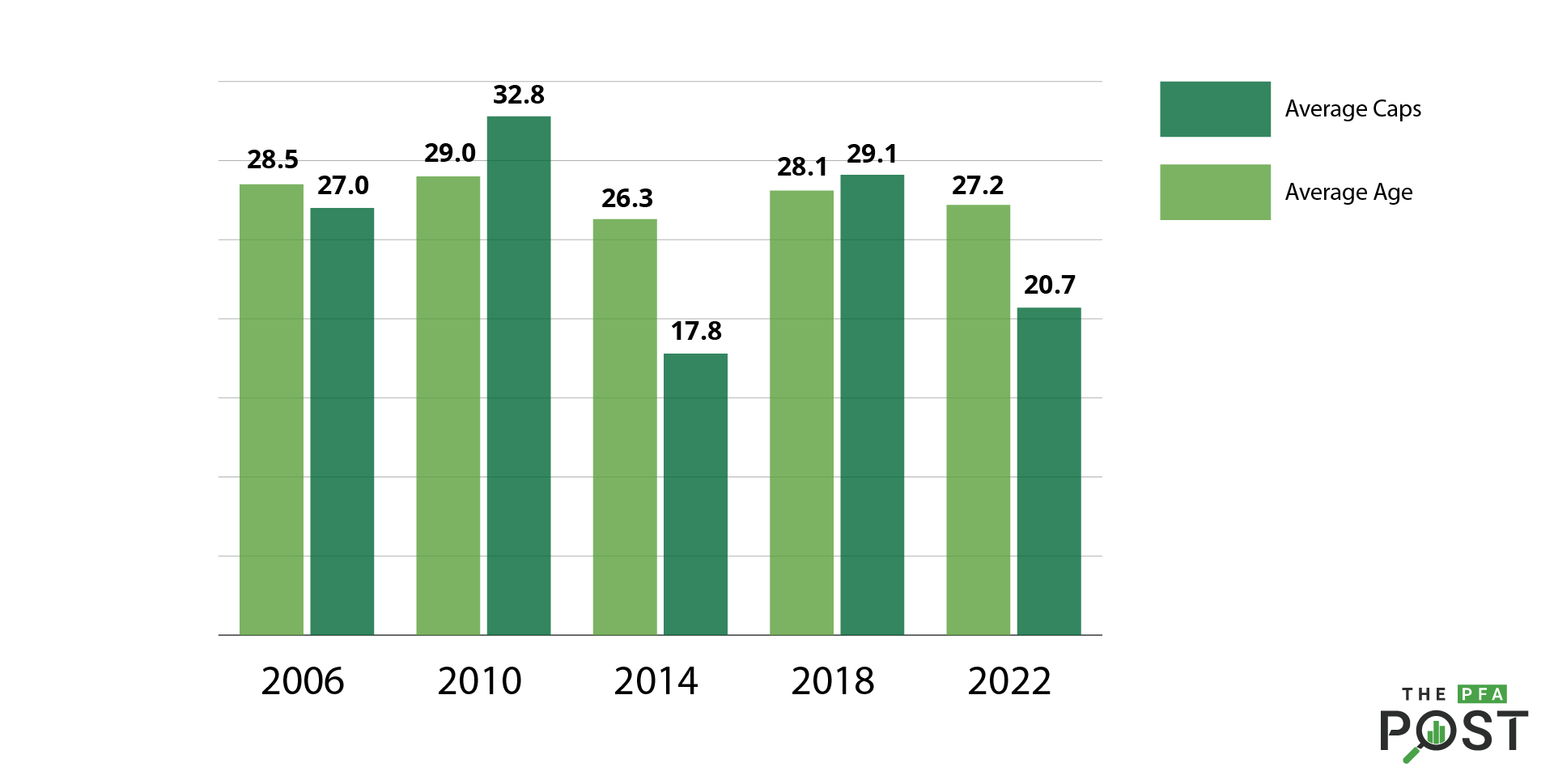

The report’s analysis of the squad selected for the tournament finds that this was the second youngest Australian squad by average age and second least experienced by average caps across our run of World Cup Finals appearances starting in 2006.

The youngest and least experienced squad was Ange Postecoglou’s 2014 Brazil cohort (counting all players, whether they made an appearance or not).

This finding contradicts a prediction made by Football Australia’s Performance Gap report, published two years before the tournament, which anticipated that Australia would have “one of its oldest squads at the FIFA World Cup Qatar 2022”.

Based on Socceroos match minutes at the time, the report said: “There will be a limited number of 24–29-year-old players in the player pool available for the FIFA World Cup Qatar 2022.”

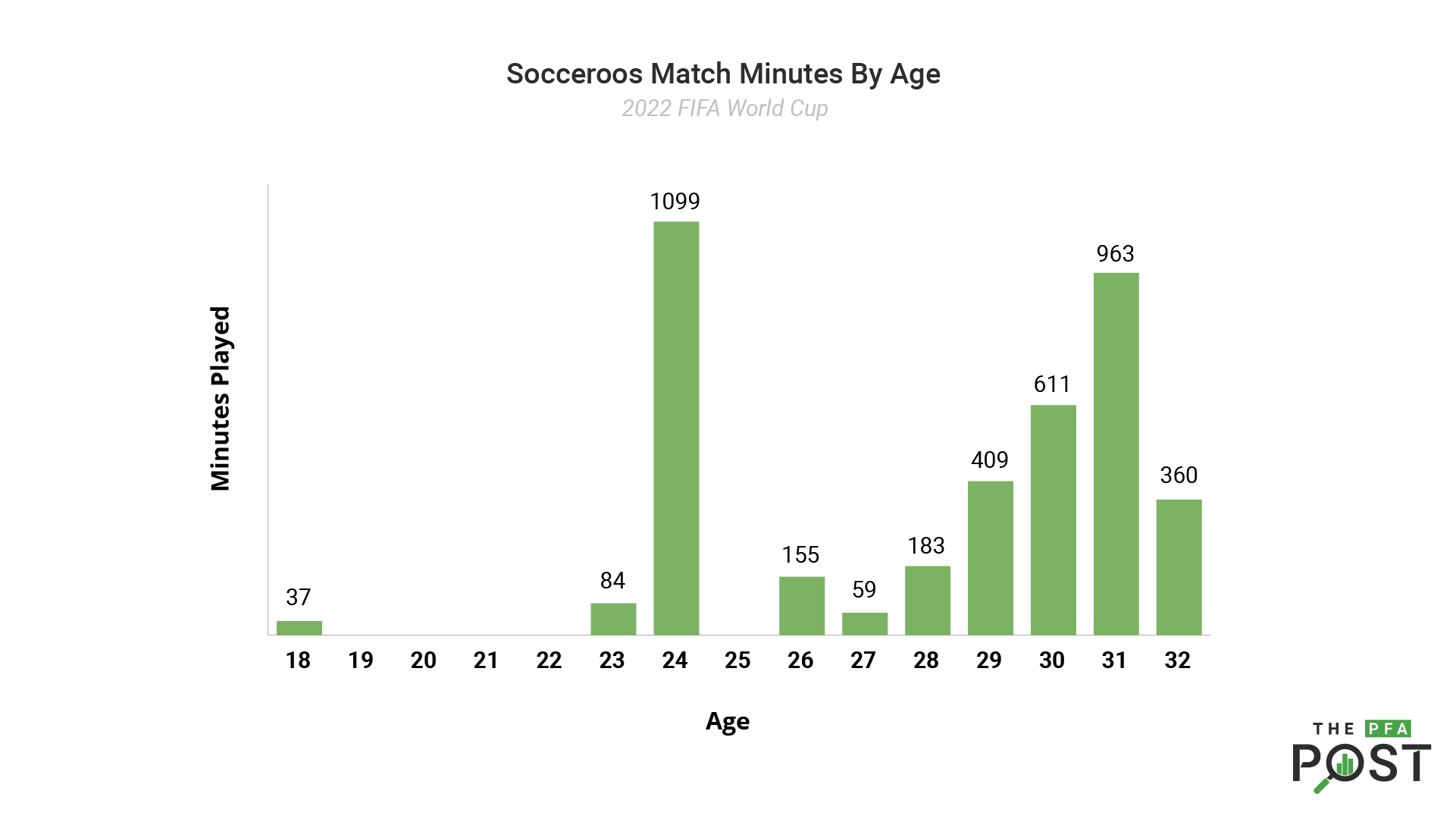

Looking at the actual minutes earned at the World Cup in Qatar, there is some hint of a relative lack of players in their late twenties, but this was offset by the emergence of several 24-year-olds who played key roles at the tournament.

The 24-year-olds who featured were Harry Souttar (360 minutes), Kye Rowles (360), Riley McGree (265), and Keanu Baccus (114). Nathaniel Atkinson was the 23-year-old, and at 18, Garang Kuol became the youngest player to feature in the Men’s World Cup knockout stages since Pelé in 1958.

This outcome prompts a revisit of recent research and discourse around the development of elite Australian men’s players.

In 2017, the PFA released its Player Pathway Study, a comprehensive audit of the careers of professional Australian footballers. Like FA’s Performance Gap report, it used match minutes as the primary unit of analysis. Among other things, it showed that Australians’ representation in the ‘Big 5’ European leagues has collapsed since the mid-2000s.

In 2019, the PFA released Culture Amplifies Talent, an unprecedented study into the developmental histories of Australia’s ‘Golden Generation’ of men’s players undertaken in conjunction with expert researchers at Victoria University.

This piece of work turned the problem on its head by focusing on what happened in our best players’ lives long before they reached the professional game. Instead of assuming that match minutes produce talented senior players, it questioned whether sufficiently talented youth players would demand match minutes.

The truth, of course, lies somewhere in the middle. Senior match minutes for young players are both an important input into player development and an output of an effective talent production line.

The implication for policymakers is that both ends of the problem require attention.

With regards to our professional competition, there are some positive signs that current settings are functional. Other than Souttar, all those breakthrough players aged 24 and under who played World Cup minutes developed in the A-League.

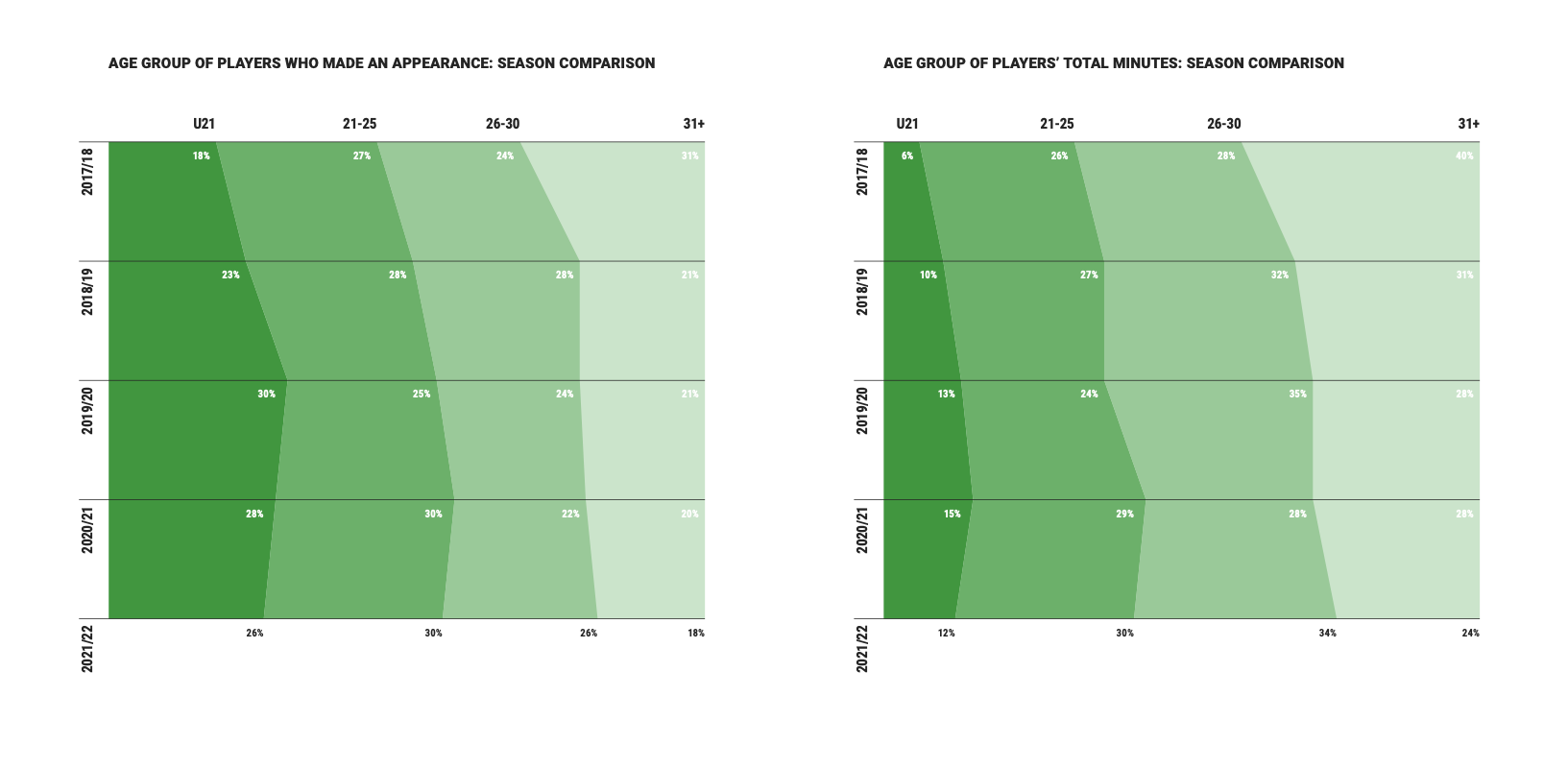

In a broader sense, since The Performance Gap was released, the age profile of the A-League Men has drastically shifted towards younger players. This trend was evident in the PFA’s 2021-22 A-League Men Report, which showed that the share of match minutes going to over 30s nearly halved from 2017 to 2022. This season’s report is due out later in the year.

One of the drivers of this shift has been clubs taking advantage of expanded Scholarship Player provisions in the 2021-26 A-Leagues Collective Bargaining Agreement.

There is more work to do. An intention of the expanded Scholarship roster was that a parallel youth or reserve league would be re-established to ensure this larger cohort of young players would get a substantial dose of competitive football while they waited for first team opportunities. This competition is still in development.

Further, as both the PFA’s and FA’s research highlighted, the A-League itself is smaller and shorter than competitor leagues, so its imminent expansion will be another positive step.

However, the importance of homegrown players to our World Cup performance shows that, at the very least, there is nothing in the A-League’s current guise which precludes good players from coming through.

Under the existing model, clubs are massively incentivised to invest in attracting and developing the best players. The upcoming Socceroos report estimates that A-League clubs will collectively receive almost US$2m in Club Benefits from FIFA for preparing players for the World Cup. This will be followed by an expected record-setting window of outbound transfers, following from Kuol’s move to Newcastle United in January.

This is why the PFA has questioned the introduction of further regulations purportedly intended to add to this incentive, which in reality will only move money around within the Australian football economy, while adding administrative burden to clubs and restricting the movement of players.

If we are failing to achieve a net increase to the game’s revenue by exploiting external opportunities such as FIFA’s Club Benefits and international transfers, we need to go back to Culture Amplifies Talent and the talent pipeline.

The backstories of some of this season’s breakthrough prospects are dripping with elements the study found to be critically important to the development of our best ever players, such as family influence, deepfelt passion, unstructured practice, and an enabling home environment.

Take the story of the Kuol brothers, raising their mum’s ire by coming home from club football and continuing to play in the backyard past dinner time.

Consider Jordan Bos’ backyard training regime (set up by dad, of course), where he honed his trademark ball-shifting and striking skills.

Count the number of Australian prospects who are the sons of professional players, led by newly capped Socceroo Alex Robertson. It’s a statistical impossibility, unless there is a causal relationship between dad’s influence at home and their development.

For the upcoming Socceroos World Cup report, we asked the squad who first got them involved in the game: 59% said it was their father. The second-highest answer was their mother, at 41%.

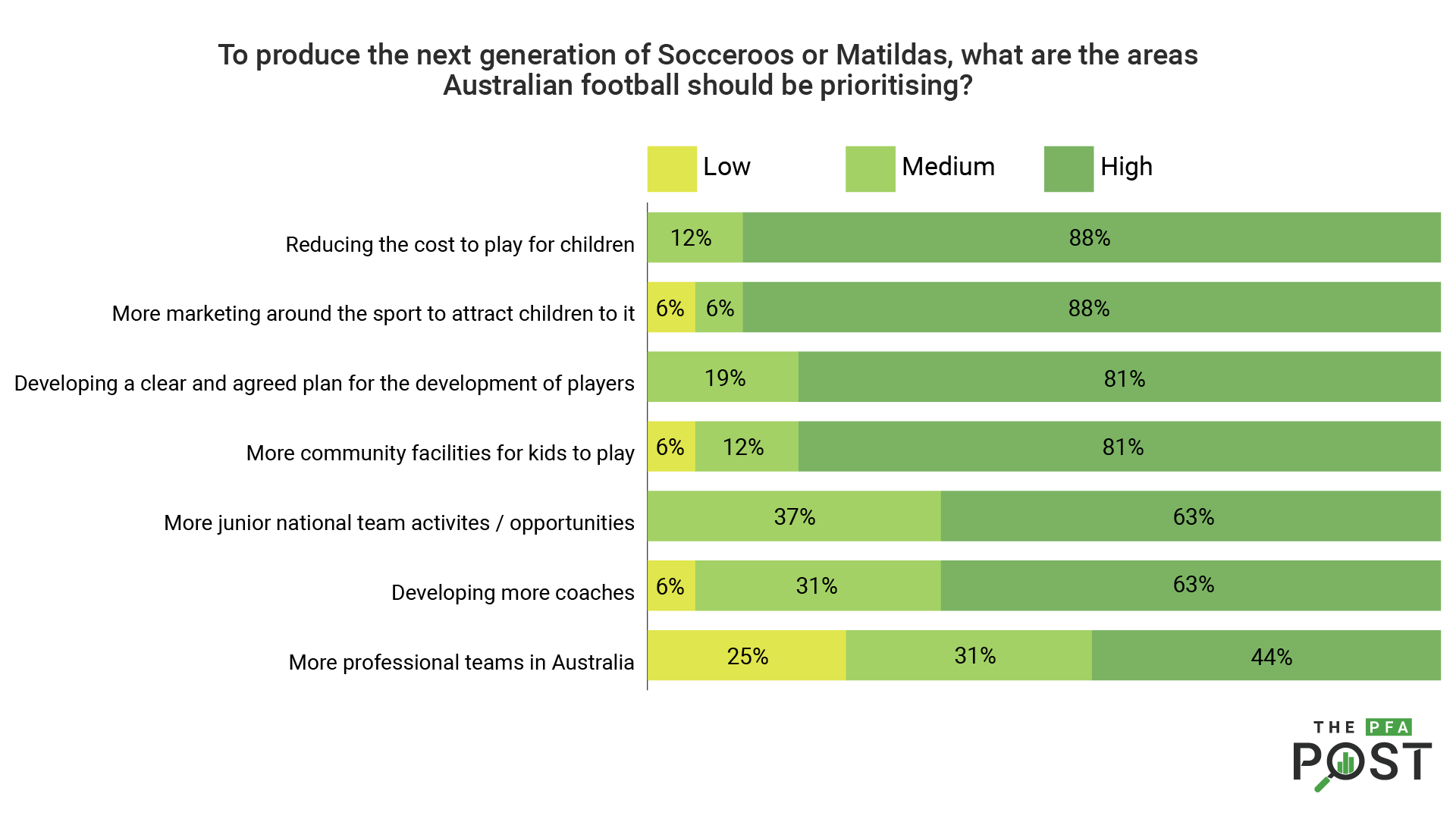

We also asked the World Cup Socceroos how high they prioritise different actions the sport could take to develop the next generation of Socceroos and Matildas. Their top answers all related to children’s connection to the sport. Their lower prioritised options – while still important – focused on the professional game.

Our emerging crop of talents shows two things: that the ‘secret sauce’ factors identified in Culture Amplifies Talent are as relevant as ever, and that the A-League is providing a platform for good-enough players to shine and progress.

The policy discussion should focus on creative solutions to bottle and replicate that secret sauce, such as ensuring our next wave of migrant communities become connected to the sport locally, giving parents resources to model an enabling home environment, and providing children in an increasingly urbanised population access to spaces for free practice with siblings and friends.

About the PFA Post

In line with the PFA’s commitment to providing policy leadership to ensure Australian football is the best governed football nation in the world, is internationally competitive on and off the field and is a central part of Australian culture, ‘The PFA Post’ analyses issues impacting Australian football.