As World Cup fever takes hold, the Matildas are breaking off-field records left, right, and centre.

The PFA and the players themselves have talked a lot about what this means for the progress of the team and women’s football more broadly.

For policymakers, another important thread is the team’s growth into a major economic engine for Australian football.

In 2020-21, the A-Leagues gained independence from Football Australia (FA), leaving a hole in the governing body’s business. The national teams are now FA’s key commercial assets. The Matildas’ increasing value, then, is as timely as it is impressive.

This PFA Post focuses on those achievements and the team’s growing importance to the Australian football economy.

How the national teams make money for the game

The main sources of recurring revenue the national teams generate for FA are broadcast, sponsorship, and match revenue. Merchandise sales are another, smaller, stream.

Then there are significant but non-recurring revenues such as tournament prize money and government grants.

The Matildas’ performance in each of these streams has grown significantly.

Broadcast: Before the World Cup, the Matildas held the record for the most-watched women’s team sports match in Australian history, set during the Tokyo Olympics in 2021. That mark was cleared by their World Cup opener against Ireland and then smashed again by the 4-0 win over Canada.

Even without Optus’ viewing figures, which aren’t disclosed, the Canada match attracted 50% more viewers than the Socceroos’ primetime World Cup fixture against Tunisia last year. It also beat out the men’s Ashes finale on the same night.

It’s almost pointless quantifying these records at the time of writing, in between the group stage and knockout rounds of the World Cup, when new heights will likely be reached.

Sponsorship: FA’s Legacy ’23 pre-tournament update says it has achieved a 150% increase in sponsorship revenue from 2020 to 2023, which it attributes in large part to the growth of the Matildas’ brand.

Match revenue: The Matildas’ attendance record has been broken twice in the past month. First, 50,629 attended the warm-up match against France at Docklands, then 75,784 watched the World Cup opener against Ireland at Homebush. More on their attendances below.

Merchandise: Nike has reported that more official Matildas jerseys had been sold before the start of the Women’s World Cup than Socceroos jerseys sold since before the Men’s World Cup last year until now.

Not all of these achievements will land directly on FA’s bottom line. Ticket sales and broadcast rights for the World Cup are received by FIFA. As the Women’s World Cup grows, Australian football will benefit from increasing prize money, grants, and Club Benefits payments.

But more importantly, the takeaway is that the Matildas have arrived as a commercial asset on par with the Socceroos, allowing FA to rebuild its post-COVID, post-A-Leagues business around powerful dual economic engines. The next time FA sits down with prospective broadcasters or partners, these metrics will power a compelling story about this team’s reach and magnetism.

Next, we’ll show that this development is not solely due to the World Cup halo effect; the Matildas’ appeal has been on a strong upwards trajectory for a long time.

Attendances: average will have doubled or tripled after World Cup

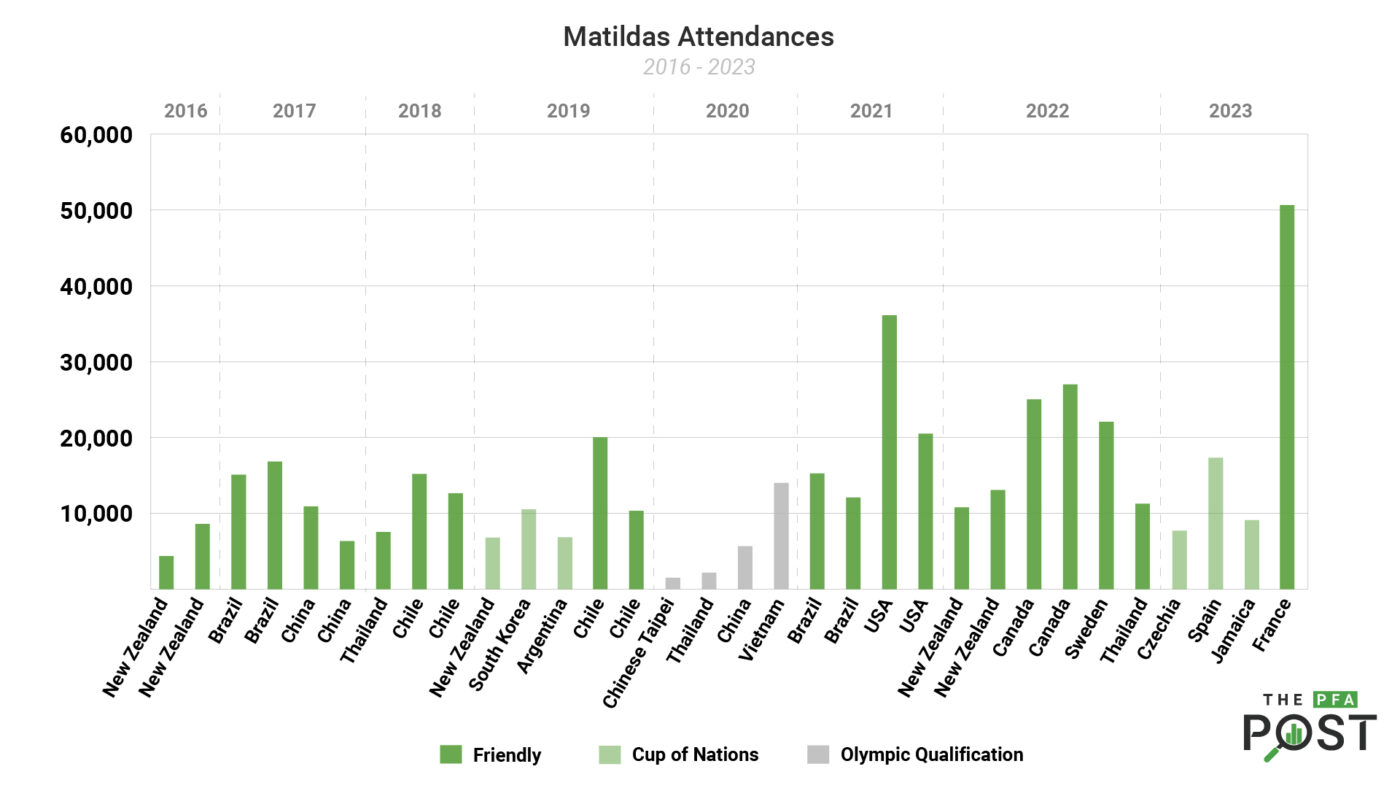

The Matildas’ average crowd has risen from 10,860 in 2016-2019 to nearly 19,852 in the last three years (including the France game, but prior to the World Cup).

This growth is despite a serious disadvantage compared to the men’s game: nearly all the Matildas’ home fixtures have been friendlies.

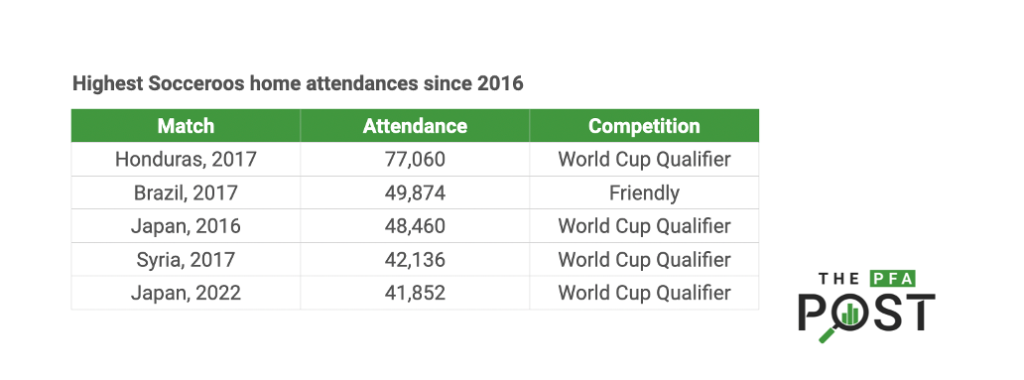

A review of the Socceroos’ home fixtures over the same period shows the importance of high-stakes World Cup qualifiers in drawing a big crowd.

Four of the five Socceroos matches to clear the 40,000 mark in that period were World Cup qualifiers, the exception being the Brazil friendly at the MCG in 2017. With respect, the likes of Honduras and Syria are unlikely to be major drawcards in their own rights. The jeopardy of competitive football is what heightens interest in those matches.

The PFA’s report on the Socceroos’ 2022 World Cup campaign flagged that the pandemic denied that team at least seven home matches, including the World Cup qualifying playoffs which had been the highest attended fixtures in the previous cycle.

For women, the peak continental tournaments such as the AFC Asian Cup generally double as World Cup qualifiers. Only Europe holds separate, specific qualifiers like the men.

FIFPRO has recently released a report criticising this policy, calling for standalone qualifiers worldwide to drive women’s football development through more high-quality, high-stakes matches.

When considering both the trajectory of Matildas fandom and the importance of competitive stakes to Socceroos support, it’s clear that shifting to standalone Women’s World Cup qualifiers would give Australian football a whole new suite of valuable ‘content’ (as well as sporting benefits).

Nonetheless, even in the current paradigm, the Matildas have become box office.

Brand: Matildas join Socceroos as one of Australia’s most-loved teams

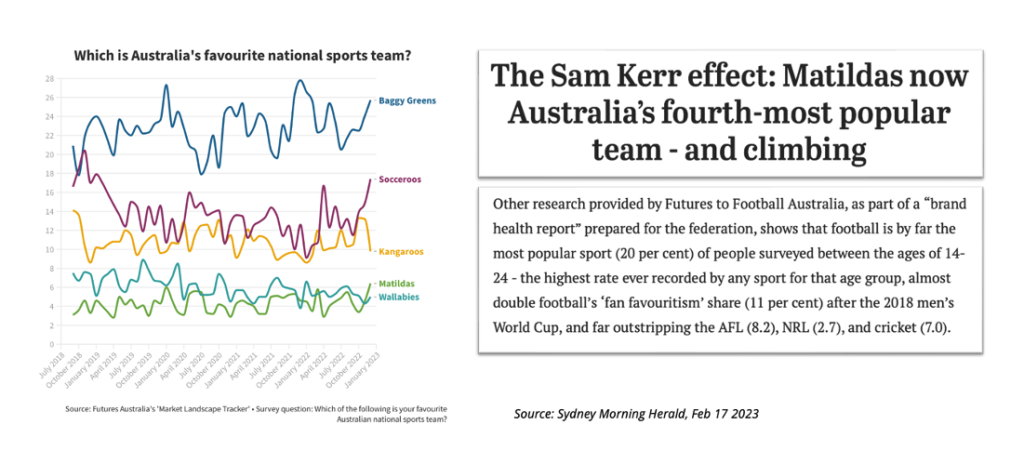

Both the PFA and FA have recently commissioned independent research into the national team brands, and both sets of findings reflect the same upwards trajectory as attendances, tracing back well before the Women’s World Cup.

FA released parts of its research from Futures Australia earlier this year. It showed that the Matildas had overtaken the Wallabies to become Australia’s fourth favourite national team, and predicted they would join the Socceroos in the top three after the Women’s World Cup.

The PFA’s research was conducted by Gemba before the 2022 Men’s FIFA World Cup. It found a similar ranking of national teams and similar trendlines. On Gemba’s ‘Asset Power’ metric, the Matildas were actually ranked second behind men’s cricket, having increased their score by 136% since 2015.

Evidently, the Matildas’ ascension is not just a World Cup-inspired flash in the pan, but a product of a long-established trend.

The bottom line: Matildas’ economic value must be recognised

The national teams currently contribute between one third and half of FA’s revenues. This doesn’t include indirect sources such as amateur player registration fees, which are projected to increase on the back of the national teams’ achievements.

Due to the Matildas’ growing popularity, this proportion will likely increase over the next four-year cycle. FA’s annual revenues should return to the nine-figure levels last seen when the A-Leagues were under its control.

In light of this growing importance of the national teams to the governing body’s business, it is an opportune moment to reflect on the structure of the players’ financial partnership with FA.

In the 2019-2023 National Teams Collective Bargaining Agreement (CBA), a gender-equal, revenue-share model was established for the first time. How it works is: all revenue the two national teams generate through the aforementioned categories is put into one big pool, of which a set percentage is allocated to player payments (revenue-share). Regardless of which team earned the revenue, the pool is distributed 50-50 across the two teams (gender equality).

Gender equality: Paying men and women equally is the right thing to do. Further, it creates a positive aura around the teams and the industry. But it also makes both teams invested in the success of the other. The market research reinforces this model; Gemba found that over half of Socceroos fans are also Matildas fans, and more than four-fifths of Matildas fans are also Socceroos fans. Futures Sport and Entertainment president Simon Wardle said Australian football would benefit from the “double whammy” of the Socceroos’ performance in Qatar and the anticipation of the home Women’s World Cup.

Revenue-share: This aspect of the CBA structure creates an interdependent relationship between the players and FA, incentivising both parties to work towards collective success. The players entrust FA with their collective image rights in the knowledge that maximising the rights’ value is in FA’s self-interest. FA knows players are bought in to a program in which they retain a share of upside they contribute to.

A precondition for the success of such a model must be that the players are paid a fair share of the revenue they generate.

On a sliding scale, the lower the percentage share, the less the players’ incentive to grow the pie.

And there is a threshold below which the players’ participation is not economically justified. The reason is that by providing the governing body with their collective image rights, the players restrict themselves from doing individual commercial deals in the same product categories.

This occurs against a backdrop of a sports marketing industry shifting towards a more player-centric paradigm. As Futures president Simon Wardle explained:

“What we’re seeing from a lot of the research that Futures does is that ‘hero worship’ to that star player is becoming more and more of an important factor for fans engaging with sports. A lot of that is being driven by the fact that, especially when you look at those younger fans, the Gen Z fans, more of their consumption is through non-traditional [media], social, digital. They’re engaging with the players ahead of, or as well as, the teams.”

To illustrate the point, Sam Kerr (1.2m) and Ellie Carpenter (240k) have more Instagram followers than the official Matildas account (230k). The World Cup squad’s combined followship is 2.42m, more than ten times the team’s reach.

There is an opportunity cost in the current CBA structure, particularly for the highest-profile players. For players to agree to limit their ability to freely monetise these platforms, the collective deal has to be sufficiently valuable.

The national teams CBA is due for renegotiation after the Women’s World Cup. When the 2019-2023 deal was bargained, the achievements outlined in this Post were unfulfilled potential. Now, the Matildas have proved their worth.